ADHD, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects both children and adults. It is characterized by signs such as difficulty with focus, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

ADHD can make it challenging to complete tasks, follow through on responsibilities, and interact with others.

It is common for everyone to experience some level of difficulty with attention or controlling impulsive behavior, but for those with ADHD, this can be so pervasive and persistent that it can interfere with every aspect of their lives.

ADHD is often diagnosed in childhood but can also be diagnosed later in life. It is common for many people to recognize they have ADHD later in life or go their whole lives without a formal diagnosis.

While the signs of ADHD can change with time, they can still interfere with an individual’s functioning, specifically in their relationships, health, work, and finances.

The first known documentation of ADHD was from 1902, when it was coined for some children. Since then, the condition has been given numerous names, one of these being attention deficit disorder (ADD) which is now an outdated term.

Key Takeaways

- ADHD Defined: A neurodevelopmental disorder marked by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that affects daily life. The condition can be diagnosed in childhood or adulthood, with signs sometimes changing over time.

- Diagnosis and Causes: ADHD is diagnosed by medical professionals, including psychiatrists and pediatricians, through a comprehensive assessment. The disorder is believed to have genetic and neurological origins, with research pointing to brain structure differences and dopamine levels as potential contributing factors.

- Co-existing Conditions: More than two-thirds of people with ADHD have at least one co-existing condition. Common co-existing conditions include mood disorders, anxiety, autism, and tic disorders like Tourette syndrome.

- Management: While lifelong, ADHD can be effectively managed with medication, therapy, and self-help strategies. Treatment can include stimulant medications to increase dopamine and behavioral therapies like CBT to help manage symptoms.

Signs of ADHD

It’s important to understand that experiencing some signs of ADHD does not automatically mean someone has the disorder. Many ADHD signs can be common and relatable, but they do not necessarily indicate ADHD.

Additionally, individuals with ADHD may not exhibit all signs or traits and may have varying levels of each trait depending on the situation.

Inattention & Focus Issues 🧠

- Easily distracted, such as ‘zoning out’ during conversations or switching focus during tasks.

- May miss important information because they have ‘zoned out’.

- Often forgetful, for example, they may forget birthdays, instructions, or homework.

- Hyper-focusing on tasks that interest them, to the detriment of basic needs like eating and sleeping.

- Executive dysfunction, which is difficulty executing and completing tasks from start to finish.

Hyperactivity & Impulsivity ⚡️

- Hyperactivity, such as not being able to sit still or having racing thoughts.

- Impulsivity, which can manifest as reckless spending or interrupting others.

- Have a low tolerance for boredom and need a lot of stimulation.

Emotional & Functional Challenges 😟

- Time management difficulties, like getting to appointments on time and procrastinating on important tasks.

- Difficulties regulating emotions, such as managing strong emotions which can sometimes result in outbursts.

- Motivational issues.

- Low self-esteem after years of not meeting their and other people’s expectations.

- Trouble with sleep, including getting to sleep, staying asleep, and waking up on time.

How is ADHD diagnosed?

Below is some information on the diagnosis process. Please note that this article is for informational purposes only and should not be used as a diagnostic tool for ADHD.

What kind of doctor diagnoses ADHD?

ADHD can be diagnosed by a variety of medical and mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, pediatricians, psychologists, and, in some cases, primary care providers.

Psychiatrists and other specialists are particularly helpful in making a diagnosis and managing treatment, especially if co-occurring conditions are present.

It is important to find a professional with experience in diagnosing and treating ADHD.

What tests or assessments are used to diagnose ADHD?

The diagnosis is based on a comprehensive assessment that includes:

- Symptom Checklists and Rating Scales: Professionals use standardized criteria, such as those from the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), to determine if a person meets the required number of symptoms for inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity.

- Information Gathering: The clinician will conduct interviews with the person and, if possible, with family members, friends, or teachers to get a detailed history of symptoms and how they affect daily life.

- Medical Exam: A medical exam may be performed to rule out other conditions that could be causing similar symptoms, such as thyroid problems, anxiety, depression, or learning disabilities.

- Childhood History: Since ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder, symptoms must have been present in childhood, typically before age 12. For adults, this means the clinician will gather information about their childhood behavior from them and others who knew them well.

Can I get diagnosed with ADHD as an adult?

Yes, adults can be diagnosed with ADHD.

The diagnostic process for adults is similar to that for children, but it requires a thorough review of past and present symptoms to confirm that they began in childhood and are not caused by another condition.

The criteria for adults and adolescents ages 17 and older require a person to have at least five symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity, as opposed to the six symptoms required for children.

Many people may not be diagnosed until adulthood due to a lack of awareness or other conditions masking their symptoms.

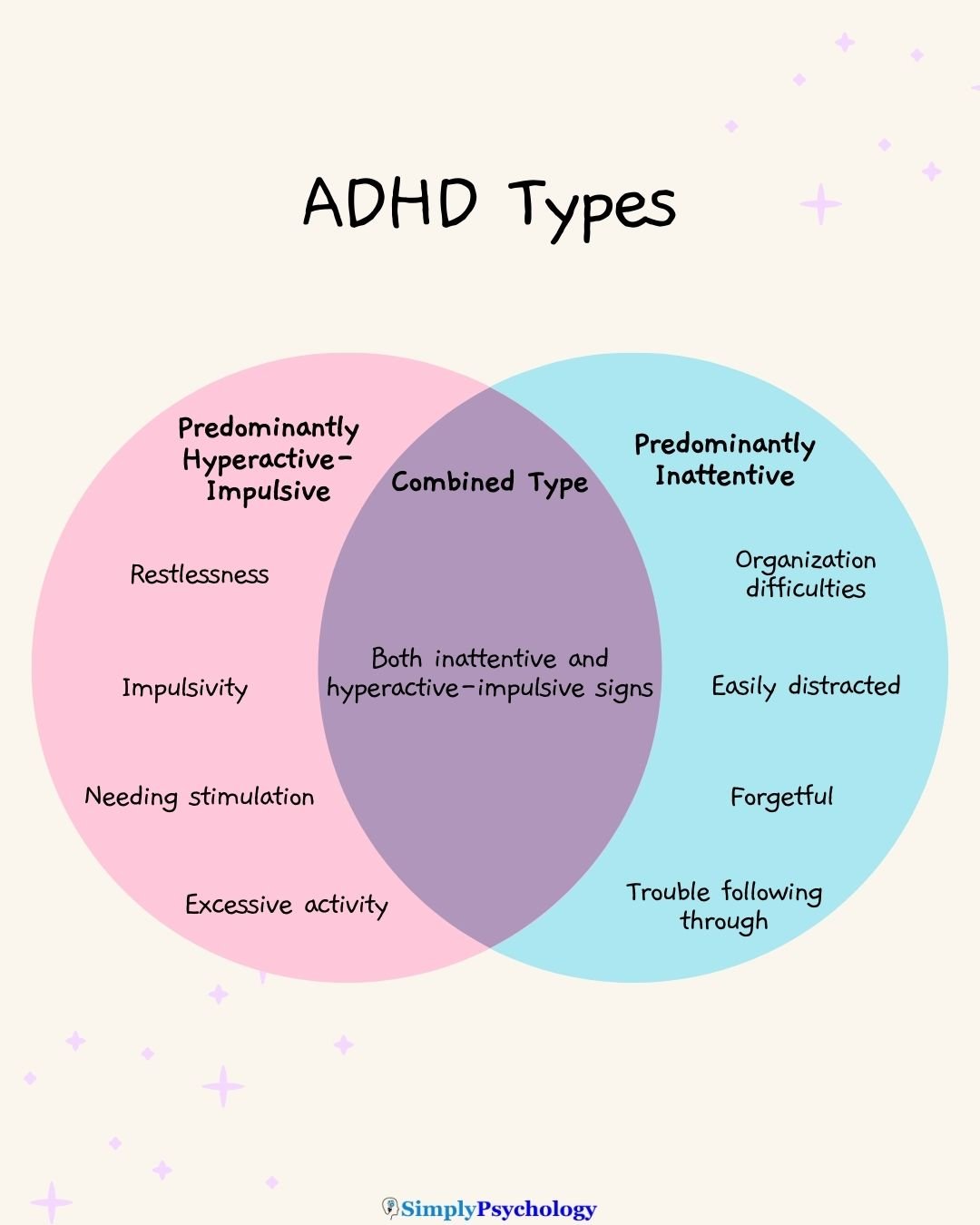

ADHD types

The DSM-5 criteria for ADHD list three types of ADHD:

- Predominantly inattentive type

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type

- Combined hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive type.

Below are the types and some of the traits associated with each one:

Predominately inattentive type

The predominantly inattentive type of ADHD is characterized by difficulties in maintaining focus, following instructions, and organizing tasks, often resulting in forgetfulness and distractibility.

Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type

The predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type of ADHD is characterized by excessive activity, restlessness, impulsivity, and difficulty waiting or taking turns, often leading to disruptive behavior.

Combined hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive type

The combined hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive type of ADHD is characterized by a significant presence of both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, leading to challenges in multiple areas of functioning.

ADHD In Girls And Women

While ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in males than females, with a typical ratio of 3:1, this discrepancy suggests that many girls with ADHD remain unidentified and untreated, leading to long-term social, educational, and mental health consequences.

A 2020 consensus summarized key points for the detection of ADHD in females:

- Females present with both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive signs, although hyperactive-impulsive signs may be less severe or noticeable than in males.

- Emotional issues, such as low mood, emotional lability, anxiety, and emotional regulation problems, may be more common or severe in females with ADHD.

- Girls with ADHD are vulnerable to bullying, increased school drop-out, academic underachievement, and decreased self-esteem and self-concept.

- They may not show as many behavioral problems commonly associated with males, and compensatory behaviors may mask behaviors and difficulties.

- Dysfunctional coping strategies, such as alcohol or drug use, may be used to deal with emotional problems, social isolation, and rejection.

Girls and women with ADHD may become skilled at camouflaging their struggles using compensatory strategies, leading to an underestimation of their underlying problems.

Consequently, females with ADHD are often treated for anxiety or depression before receiving an ADHD diagnosis.

It is crucial not to discount ADHD in females simply because they may not display the stereotypical idea of an ADHD boy who “bounces off the walls.”

What Causes ADHD?

The cause of ADHD likely cannot be tied to a single factor but is likely due to a complex combination of multiple factors that alter brain chemistry and structure:

Genetics

There is uncertainty surrounding the causes of ADHD, although it is generally believed to have neurological and genetic origins.

This means that if someone has ADHD, there is a good chance that they have a family member who also has ADHD.

Brain differences

Research suggests that there is a structural difference in the brains of those with ADHD compared to those who do not have the condition.

It was found that those with ADHD had reduced grey matter volumes in their anterior cingulate cortex, occipital cortex, cerebellar regions, and bilateral hippocampus/amygdala.

This reduction in grey matter volume could explain why people with ADHD have attentional problems, since grey matter is involved in learning, memory, cognitive processes, and attention.

However, whether ADHD is the cause or effect of these brain differences is debatable.

Environmental factors

There are believed to be some factors in the environment that may increase the likelihood of someone having ADHD:

- Exposure to lead or pesticides in early childhood

- Premature birth or low weight at birth

- Brain injury

It has been believed in the past that certain environmental factors may cause ADHD, although these have not been found to be the case.

Some of the factors that do NOT cause ADHD include watching excessive amounts of TV, eating sugar, family stress, parenting styles, and traumatic experiences.

Even though environmental factors such as family stress do not cause ADHD, they can change the way ADHD presents itself and may result in additional problems such as anti-social behaviors.

Researchers are continuing to study the exact relationship between ADHD and environmental factors but point out that there is no single cause that can account for all cases of ADHD.

Dopamine levels

Underlying differences in the brain are likely to be an underlying cause of ADHD, with some researchers looking at dopamine as a possible contributor.

Dopamine is a chemical of the brain that regulates emotional responses and is involved in motivation, feelings of pleasure, and rewards.

People with ADHD may have different levels of dopamine compared to people without ADHD.

Studies suggest that one of the reasons for this difference is that people with ADHD have more of a protein called dopamine transporters in their brains. These proteins can reduce dopamine levels in the brain, which may contribute to ADHD signs.

Studies also suggest that the dopamine pathway involved in reward and motivation may play a role in ADHD.

While more research is needed, some studies have found that a specific type of dopamine transporter may affect certain traits of ADHD, such as mood instability.

Co-existing conditions

More than two-thirds of people who have ADHD also have at least one other co-existing condition.

Occasionally, ADHD may overshadow other conditions, making it harder to notice.

Likewise, the other condition may overshadow ADHD, meaning that ADHD can go undiagnosed in some.

Mood disorders

Studies suggest that up to 53.3% of adults with ADHD may also have depression.

Approximately 14% of children with ADHD have depression compared to 1% of children without ADHD. Up to 20% of those with ADHD may also show signs of bipolar disorder.

Typically, the ADHD signs will occur first, followed by the mood disorder, perhaps because of the struggles those with ADHD face.

Anxiety

It is common for people with ADHD to also have a co-existing anxiety disorder. Some anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

People with ADHD may find it difficult to keep up with daily tasks and make and maintain relationships, so this could increase anxious feelings as a result.

Likewise, people with ADHD are more likely to experience an anxiety disorder compared to those without ADHD.

Autism

Autism is characterized by differences in social communication, social interaction, and behavior, with a wide range of characteristics such as sensory differences, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors.

Autism and ADHD are believed to commonly co-occur. It is unclear precisely how common it is, but scientific literature suggests 50-70% of autistic individuals may have co-occurring ADHD.

Tic and Tourette syndrome

It is common for those with Tourette syndrome to have coexisting ADHD.

Tics include sudden, rapid, involuntary movements or vocalizations. Tourette syndrome is rarer but most severe, involving making involuntary noises or movements on an almost daily basis for years.

These extra challenges can make it harder for a child to manage at school and can worsen feelings of anxiety and depression.

Can ADHD be managed?

ADHD is a lifelong condition that can be effectively managed through various approaches, including medication, therapy, and self-help strategies.

While there is no single solution, a combination of methods often works best to help individuals navigate daily life.

Always consult a healthcare professional for personalized guidance.

Medication

Medications for ADHD are primarily divided into two types: stimulants and non-stimulants.

- Stimulant medications, such as Ritalin, Adderall, and Vyvanse, can help improve focus by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. They can, however, have side effects, including sleep or heart problems.

- Non-stimulant medications, like Wellbutrin and Strattera, are less commonly prescribed and may be used for those with co-occurring severe anxiety. They work by increasing the levels of certain neurotransmitters in the brain.

Therapy

- Behavioral therapy helps individuals learn skills to manage their ADHD symptoms. The goal is to develop more effective strategies to address areas like organization, focus, and impulse control. This can make it easier to navigate school, work, and relationships.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is another effective option. It helps individuals recognize how their thoughts influence their behaviors, allowing them to reframe thought patterns and better manage their symptoms. CBT can also assist with co-occurring conditions, such as mood and anxiety disorders.

ADHD Coaching

ADHD coaching is another valuable tool that helps individuals manage their daily lives.

A coach works with you to build on your strengths and develop new skills to better handle challenges with time management, organization, and goal-setting.

It provides a structured, supportive partnership focused on practical strategies for navigating your specific needs.

The Value of a Support Network

Connecting with others who have ADHD or who are neurodivergent can be a powerful way to manage the condition.

Building a support network, whether through online communities or local groups, can provide a sense of belonging and help you feel more comfortable with who you are.

Sharing tips, experiences, and struggles with others who understand can reduce feelings of isolation and improve self-esteem.

Self-Help Strategies

In addition to formal treatment, many individuals use self-help methods to cope with ADHD symptoms.

These practical strategies can help with personal struggles, such as managing your daily life and relationships:

- Structure and Routine: Creating a consistent daily schedule with regular expectations, making lists, and using a calendar can help reduce forgetfulness and manage time.

- Task Management: Breaking large tasks into smaller, more manageable parts can help prevent feeling overwhelmed. Taking regular breaks is also helpful for maintaining focus and letting out energy.

- Lifestyle Adjustments: Engaging in regular exercise can help stimulate the brain, improve focus, and reduce impulsivity. Regulating sleep patterns by reducing sugar, caffeine, and screen time can also help manage symptoms.

- Mindfulness: Practicing breathing exercises, yoga, meditation, or spending time outdoors can help calm an overactive mind and ease symptoms.

If you are someone who has ADHD, you might find that you structure your life in a way that might be less conventional but works for your brain. Even small accommodations at home or the workplace can make a huge difference to your quality of life.

Further Reading

References

Al-Yagon, M., & Walter, E. (2025). Exploring pathways to resilience and well-being for young adults with/without ADHD in higher education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 1–18.

Anker, E., Ogrim, G., & Heir, T. (2022). Verbal working memory and processing speed: Correlations with the severity of attention deficit and emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD. Journal of Neuropsychology, 16(1), 211-235.

Baltes-Flueckiger, L., Wagner, A., Sattler, I., Meyer, M., Tschopp, A., Walter, M., & Colledge, F. How depression and ADHD relate to exercise addiction: A crosssectional study among frequent exercisers. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1427514.

Bonath, B., Tegelbeckers, J., Wilke, M., Flechtner, H. H., & Krauel, K. (2018). Regional gray matter volume differences between adolescents with ADHD and typically developing controls: further evidence for anterior cingulate involvement. Journal of attention disorders, 22( 7), 627-638.

Centers for Disease control and Prevention. (2021, September 23). Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/diagnosis.html.

Dougherty, D. D., Bonab, A. A., Spencer, T. J., Rauch, S. L., Madras, B. K., & Fischman, A. J. (1999). Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Lancet, 354 (9196), 2132-2133.

French, B., Nalbant, G., Wright, H., Sayal, K., Daley, D., Groom, M. J., Cassidy, S., & Hall, C. L. (2024). The impacts associated with having ADHD: an umbrella review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 15, 1343314.

Grimm, O., Kranz, T. M., & Reif, A. (2020). Genetics of ADHD: what should the clinician know?. Current psychiatry reports, 22, 1-8.

Hours, C., Recasens, C., & Baleyte, J. M. (2022). ASD and ADHD comorbidity: What are we talking about?. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 837424.

Jeong, S. H., Choi, K. S., Lee, K. Y., Kim, E. J., Kim, Y. S., & Joo, E. J. (2015). Association between the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-related traits in healthy adults. Psychiatric genetics, 25 (3), 119-126.

Johansen, E. B., Killeen, P. R., Russell, V. A., Tripp, G., Wickens, J. R., Tannock, R., Williams, J. & Sagvolden, T. (2009). Origins of altered reinforcement effects in ADHD. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 5 (1), 1-15.

Katzman, M. A., Bilkey, T. S., Chokka, P. R., Fallu, A., & Klassen, L. J. (2017). Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC psychiatry, 17 (1), 1-15.

Koyuncu, A., Ayan, T., İnce Guliyev, E., Erbilgin, S., & Deveci, E. (2022). ADHD and anxiety disorder comorbidity in children and adults: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(2), 129-140.

Lachance, K., & Gosselin, N. (2025). Listening habits and subjective effects of background music in young adults with and without ADHD. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1508181.

Langley, K., Fowler, T., Ford, T., Thapar, A. K., Van Den Bree, M., Harold, G., … & Thapar, A. (2010). Adolescent clinical outcomes for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196 (3), 235-240.

Lee, G. J., Do, C., & Suhr, J. (2023). Noncredible presentations of symptoms and functional impairment in the assessment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychology & Neuroscience, 16(3), 284–301.

Moreno-García, I., Meneres-Sancho, S., Camacho-Vara de Rey, C., & Servera, M. (2019). A randomized controlled trial to examine the posttreatment efficacy of neurofeedback, behavior therapy, and pharmacology on ADHD measures. Journal of attention disorders, 23(4), 374-383.

National Resource Center on ADHD. (2017). About ADHD. CHADD. https://chadd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/aboutADHD.pdf

Rothenberger, A., & Heinrich, H. (2022). Co-Occurrence of Tic Disorders and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder—Does It Reflect a Common Neurobiological Background?. Biomedicines, 10(11), 2950.

Russell, A. E., Benham‐Clarke, S., Ford, T., Eke, H., Price, A., Mitchell, S., Newlove-Delgado, T., Moore, D., & Janssens, A. (2023). Educational experiences of young people with ADHD in the UK: Secondary analysis of qualitative data from the CATCh‐uS mixed‐methods study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(4), 941-959

Sedgwick, J. A., Merwood, A., & Asherson, P. (2019). The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11, 241-253.

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Newcorn, J. H., Telang, F., Fowler, J. S., Zhu, W., Logan, J., Ma, Y., Pradhan, K., Wong, C. & Swanson, J. M. (2009). Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications. Jama, 302 (10), 1084-1091.e

Young, S., Adamo, N., Ásgeirsdóttir, B. B., Branney, P., Beckett, M., Colley, W., Cubbin, S. Deeley, Q., Farrag, E., Gudjonsson, G., Hill, P., Hollingdale, J., Kilic, O., Lloyd, T., Mason, P., Paliokosta, E., Perecherla, S., Sedgwick, J., Skirrow, C., Tierney, K., van Rensburg, K. & Woodhouse, E. (2020). Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC psychiatry, 20 (1), 1-27.

Zhang, S. H., Yang, T. X., Wu, Z. M., Wang, Y. F., Lui, S. S., Yang, B. R., & Chan, R. C. (2024). Identifying subgroups of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder from the psychopathological and neuropsychological profiles. Journal of Neuropsychology, 18(1), 173-189.