The experimental method involves the manipulation of variables to establish cause-and-effect relationships. The key features are controlled methods and the random allocation of participants into controlled and experimental groups.

What is an Experiment?

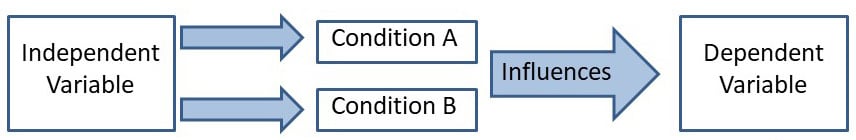

An experiment is an investigation in which a hypothesis is scientifically tested. An independent variable (the cause) is manipulated in an experiment, and the dependent variable (the effect) is measured; any extraneous variables are controlled.

An advantage is that experiments should be objective. The researcher’s views and opinions should not affect a study’s results. This is good as it makes the data more valid and less biased.

Types

There are three types of experiments you need to know:

1. Lab Experiment

A laboratory experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter manipulates one or more independent variables and measures the effects on the dependent variable under controlled conditions.

A laboratory experiment is conducted under highly controlled conditions (not necessarily a laboratory) where accurate measurements are possible.

The researcher uses a standardized procedure to determine where the experiment will take place, at what time, with which participants, and in what circumstances.

Participants are randomly allocated to each independent variable group.

Examples are Milgram’s experiment on obedience and Loftus and Palmer’s car crash study.

- Strength: It is easier to replicate (i.e., copy) a laboratory experiment. This is because a standardized procedure is used.

- Strength: They allow for precise control of extraneous and independent variables. This allows a cause-and-effect relationship to be established.

- Limitation: The artificiality of the setting may produce unnatural behavior that does not reflect real life, i.e., low ecological validity. This means it would not be possible to generalize the findings to a real-life setting.

- Limitation: Demand characteristics or experimenter effects may bias the results and become confounding variables.

2. Field Experiment

A field experiment is a research method in psychology that takes place in a natural, real-world setting. It is similar to a laboratory experiment in that the experimenter manipulates one or more independent variables and measures the effects on the dependent variable.

However, in a field experiment, the participants are unaware they are being studied, and the experimenter has less control over the extraneous variables.

Field experiments are often used to study social phenomena, such as altruism, obedience, and persuasion. They are also used to test the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings, such as educational programs and public health campaigns.

An example is Holfing’s hospital study on obedience.

- Strength: behavior in a field experiment is more likely to reflect real life because of its natural setting, i.e., higher ecological validity than a lab experiment.

- Strength: Demand characteristics are less likely to affect the results, as participants may not know they are being studied. This occurs when the study is covert.

- Limitation: There is less control over extraneous variables that might bias the results. This makes it difficult for another researcher to replicate the study in exactly the same way.

3. Natural Experiment

A natural experiment in psychology is a research method in which the experimenter observes the effects of a naturally occurring event or situation on the dependent variable without manipulating any variables.

Natural experiments are conducted in the day (i.e., real life) environment of the participants, but here, the experimenter has no control over the independent variable as it occurs naturally in real life.

Natural experiments are often used to study psychological phenomena that would be difficult or unethical to study in a laboratory setting, such as the effects of natural disasters, policy changes, or social movements.

For example, Hodges and Tizard’s attachment research (1989) compared the long-term development of children who have been adopted, fostered, or returned to their mothers with a control group of children who had spent all their lives in their biological families.

Here is a fictional example of a natural experiment in psychology:

Researchers might compare academic achievement rates among students born before and after a major policy change that increased funding for education.

In this case, the independent variable is the timing of the policy change, and the dependent variable is academic achievement. The researchers would not be able to manipulate the independent variable, but they could observe its effects on the dependent variable.

- Strength: behavior in a natural experiment is more likely to reflect real life because of its natural setting, i.e., very high ecological validity.

- Strength: Demand characteristics are less likely to affect the results, as participants may not know they are being studied.

- Strength: It can be used in situations in which it would be ethically unacceptable to manipulate the independent variable, e.g., researching stress.

- Limitation: They may be more expensive and time-consuming than lab experiments.

- Limitation: There is no control over extraneous variables that might bias the results. This makes it difficult for another researcher to replicate the study in exactly the same way.

Ecological validity

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables which are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. EVs should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of participating in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.