Humanistic psychology is an approach that focuses on individual potential and personal growth.

It emphasizes free will, self-actualization, and the importance of a supportive environment for psychological well-being.

Pioneered by figures like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, it encourages understanding people as whole, unique individuals, striving to reach their fullest potential.

Key Contributions

- Fritz Perls (1940s-1950s): Developed Gestalt Therapy, emphasizing holistic self-awareness and personal responsibility, often associated with humanistic approaches.

- Abraham Maslow (1943): Developed the hierarchical theory of human motivation, famously known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, highlighting self-actualization as the ultimate psychological need.

- Carl Rogers (1946): Introduced client-centered therapy (also known as person-centered therapy), emphasizing empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence as crucial therapeutic elements.

- Rollo May (1950s-1960s): Known for integrating existential philosophy into psychology, contributing significantly to existential-humanistic psychology by focusing on meaning, anxiety, and human freedom.

- Abraham Maslow and Clark Moustakas (1957-1958): Facilitated key gatherings among psychologists interested in establishing a professional community focused on humanistic values, leading to the formation of humanistic psychology as a distinct approach.

- Establishment of the Association for Humanistic Psychology (1962): Officially founded at Brandeis University, this association provided an institutional platform for promoting humanistic approaches and research.

- Journal of Humanistic Psychology (1961): Launched as a dedicated academic journal, it became a significant medium for publishing research and theories grounded in humanistic principles.

Background

The humanistic approach in psychology developed as a rebellion against what some psychologists saw as the limitations of behaviorist and psychodynamic psychology.

The humanistic approach is thus often called the “third force” in psychology after psychoanalysis and behaviorism (Maslow, 1968).

Humanism rejected the assumptions of the behaviorist perspective which is characterized as deterministic, focused on reinforcement of stimulus-response behavior and heavily dependent on animal research.

Humanistic psychology rejected the psychodynamic approach because it is also deterministic, with unconscious irrational and instinctive forces determining human thought and behavior.

Both behaviorism and psychoanalysis are regarded as dehumanizing by humanistic psychologists.

Humanistic psychology expanded its influence throughout the 1970s and the 1980s. Its impact can be understood in terms of three major areas:

- It offered a new set of values for approaching an understanding of human nature and the human condition.

- It offered an expanded horizon of methods of inquiry in the study of human behavior.

- It offered a broader range of more effective methods in the professional practice of psychotherapy.

Summary Table

| Key Features |

|---|

| • Qualitative Research • Ideographic Approach • Personal Agency • Self-Actualisation • Subjective Experience • Holism |

| Assumptions |

|---|

| • Humans have free will; this is called personal agency. • All individuals are unique and have an innate (inborn) drive to achieve their maximum potential. • A proper understanding of human behavior can only be achieved by studying humans – not animals. • Subjective reality is the primary guide for human behavior • Psychology should study the individual case (idiographic) rather than the average performance of groups (nomothetic). • The whole person should be studied in their environmental context. • the goal of psychology is to formulate a complete description of what it means to be a human being (e.g. the importance of language, emotions, and how humans seek to find meaning in their lives). |

| Methodology |

|---|

| • Qualitative Research • Case Studies • Informal Interviews • Q-Sort Method (for congruence) • Content Analysis • Phenomenological Framework |

| Strengths |

|---|

| • Humanistic ideas have been applied to person-centered therapy • Humanistic ideas have been applied to education (open-classroom policy, life-long learning, self-directed education, and student-centered learning) • Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is widely used in health and social work as a framework for assessing clients’ needs. |

| Limitations |

|---|

| • Unscientific – subjective concepts • Ethnocentric (biased towards Western culture) • Belief in free will is in opposition to the deterministic laws of science • Subjective explanations will be distorted by Freudian defense mechanisms |

Core Principles

Humanistic psychology begins with the existential assumption that people have free will:

Personal agency is the humanistic term for the exercise of free will. Free will is the idea that people can make choices in how they act and are self-determining.

Behavior is not constrained by either past experience of the individual or current circumstances (determinism).

Personal agency refers to the choices we make in life, the paths we go down, and their consequences. Individuals are free to choose when they are congruent (Rogers) or self-actualized (Maslow).

Although Rogers believes much more in free will, he acknowledges that determinism is present in the case of conditional love because that may affect a person’s self-esteem.

In this way free will and determinism are integral to some extent in the humanistic perspective.

People are basically good, and have an innate need to make themselves and the world better:

Humanistic psychology: a more recent development in the history of psychology, humanistic psychology grew out of the need for a more positive view of human beings than was offered by psychoanalysis or behaviorism.

Humans are innately good, which means there is nothing inherently negative or evil about them (humans).

In this way the humanistic perspective takes an optimistic view of human nature that humans are born good but during their process of growth they might turn evil.

The humanistic approach emphasizes the individual’s personal worth, the centrality of human values, and the creative, active nature of human beings.

The approach is optimistic and focuses on the noble human capacity to overcome hardship, pain and despair.

People are motivated to self-actualize:

Major humanistic psychologists such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow believed that human beings were born with the desire to grow, create and to love, and had the power to direct their own lives.

Self-actualization refers to reaching one’s fullest psychological potential, achieving deep fulfillment, and experiencing genuine satisfaction and meaning in life.

Rogers and Maslow both viewed personal growth and self-fulfillment as fundamental human motivations, yet they proposed distinct pathways toward achieving self-actualization.

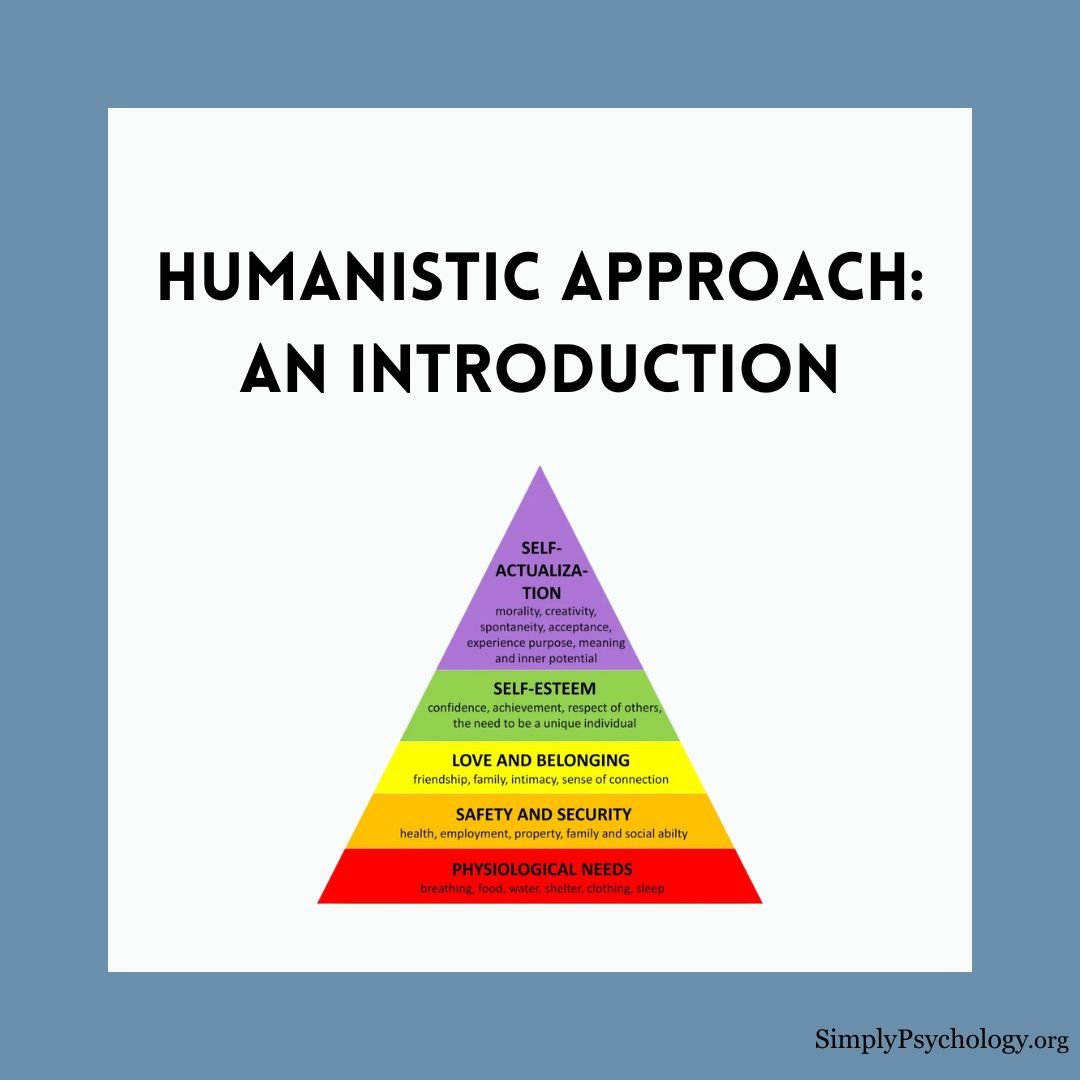

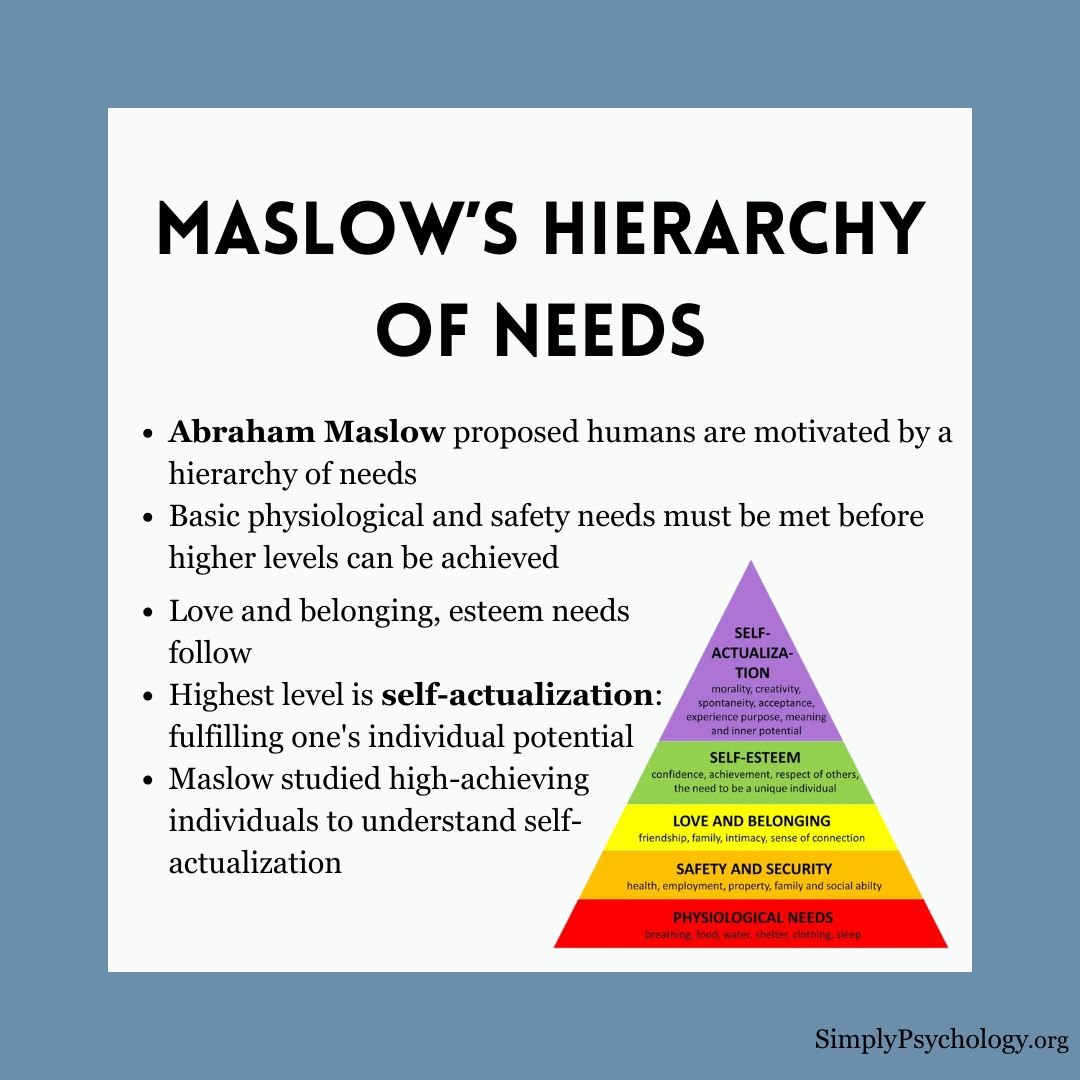

Maslow emphasized a structured progression toward self-actualization, represented in his well-known hierarchy of needs.

According to Maslow, foundational physiological needs such as food, water, and safety must first be satisfied.

Subsequently, higher-order psychological and emotional needs, such as belongingness, self-esteem, and ultimately self-actualization, can be pursued.

Maslow also introduced the concept of “peak experiences,” which are profound moments of happiness, creativity, and fulfillment that occur when an individual fully realizes their potential.

Rogers described self-actualization differently, focusing primarily on achieving congruence between one’s actual self (self-concept) and ideal self.

For Rogers, self-actualization requires individuals to develop a consistently positive view of themselves which can only occur through unconditional positive regard from others, especially from significant caregivers during childhood.

Unconditional positive regard means being valued, accepted, and respected by others without any conditions or reservations.

Rogers also introduced the notion of the fully functioning person, who continuously moves toward self-actualization by remaining open to experience, embracing life fully, trusting themselves, and living authentically.

Achieving congruence is crucial; when there is significant inconsistency between how an individual perceives themselves and their ideal self, feelings of inadequacy and diminished self-worth can arise, making self-actualization challenging or impossible.

Furthermore, Rogers and Maslow agreed that environmental factors significantly influence the journey toward self-actualization.

An environment that is supportive, affirming, and conducive to growth greatly facilitates self-actualization, while an oppressive or restrictive environment can hinder or frustrate this natural developmental process.

Behavior must be understood in terms of the subjective conscious experience of the individual (phenomenology):

Humanistic psychologists also believe that the most fundamental aspect of being human is a subjective experience.

This may not be an accurate reflection of the real world, but a person can only act in terms of their own private experience subjective perception of reality.

Humanistic psychologists argue that physical objective reality is less important than a person’s subjective (phenomenological) perception and understanding of the world.

Thus, how people interpret things internally is (for them), the only reality.

Sometimes the humanistic approach is called phenomenological. This means that personality is studied from the point of view of the individual’s subjective experience.

Meaning is the purpose or value that a person attaches to their actions or experiences

According to Rogers, we each live in a world of our own creation, formed by our processes of perception. He referred to an individual’s unique perception of reality as his or her phenomenal field.

As Rogers once said, “The only reality I can possibly know is the world as I perceive and experience it at this particular moment.

The only reality you can possibly know is the world as you perceive and experience at this moment. And the only certainty is that those perceived realities are different.

There are as many ‘real worlds’ as there are people! (Rogers, 1980, p. 102).

For Rogers, the focus of psychology is not behavior (Skinner), the unconscious (Freud), thinking (Piaget), or the human brain but how individuals perceive and interpret events.

Rogers is therefore important because he redirected psychology toward the study of the self.

Humanistic theorists say these individual subjective realities must be looked at under three simultaneous conditions.

First, they must be looked at as a whole and meaningful and not broken down into small components of information that are disjointed or fragmented like with psychodynamic theorists.

Rogers said that if these individual perceptions of reality are not kept intact and are divided into elements of thought, they will lose their meaning.

Second, they must be conscious experiences of the here and now. No efforts should be made to retrieve unconscious experiences from the past.

Phenomenenological means ‘that which appears’ and in this case, it means that which naturally appears in consciousness.

Without attempting to reduce it to its component parts – without further analysis.

Finally, these whole experiences should be looked at through introspection. Introspection is the careful searching of one’s inner subjective experiences.

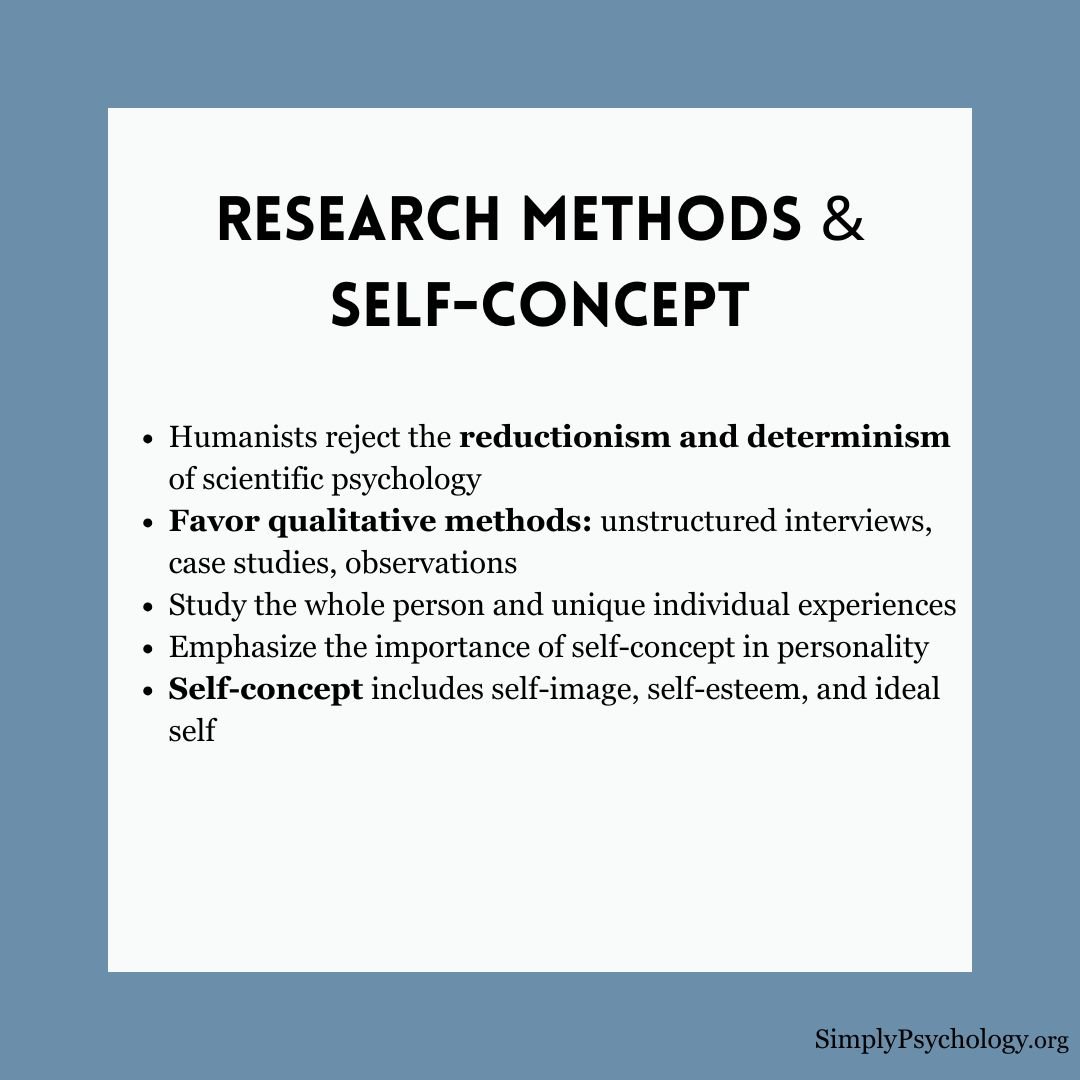

Humanism rejects scientific methodology:

Rogers and Maslow placed little value on scientific psychology, especially the use of the psychology laboratory to investigate both human and animal behavior.

Rogers said that objective scientific inquiry based on deterministic assumptions about humans has a place in the study of humans (science) but is limited in the sense that it leaves out inner human experiences (phenomenology).

Studying a person’s subjective experience is the biggest problem for scientific psychology, which stresses the need for its subject matter to be publicly observable and verifiable. Subjective experience, by definition, resists such processes.

Humanism rejects scientific methodology like experiments and typically uses qualitative research methods.

For example, diary accounts, open-ended questionnaires, unstructured interviews, and observations.

Qualitative research is useful for studies at the individual level, and to find out, in-depth, the ways in which people think or feel (e.g. case studies).

The way to really understand other people is to sit down and talk with them, share their experiences, and be open to their feelings.

Humanism rejected comparative psychology (the study of animals) because it does not tell us anything about the unique properties of human beings:

Humanism views humans as fundamentally different from other animals, mainly because humans are conscious beings capable of thought, reason, and language.

For humanistic psychologists’ research on animals, such as rats, pigeons, or monkeys held little value.

Research on such animals can tell us, so they argued, very little about human thought, behavior, and experience.

Practical Applications

The humanistic approach, though applied in fewer psychological domains compared to other approaches, has made meaningful contributions to therapy, mental health treatment, motivation, education, and personality theory.

Notably, humanistic psychology emphasizes personal growth, self-awareness, and fulfillment.

Personality

Central to Carl Rogers’ personality theory is the concept of the self, or self-concept, defined as “the organized, consistent set of perceptions and beliefs about oneself.”

The self, in humanistic psychology, represents who we genuinely are at our core, akin to an inner personality or essence, similar in function to Freud’s psyche.

Our self-concept develops through our life experiences and how we interpret these experiences.

Two major influences shaping our self-concept are early childhood experiences and how we are evaluated or perceived by others.

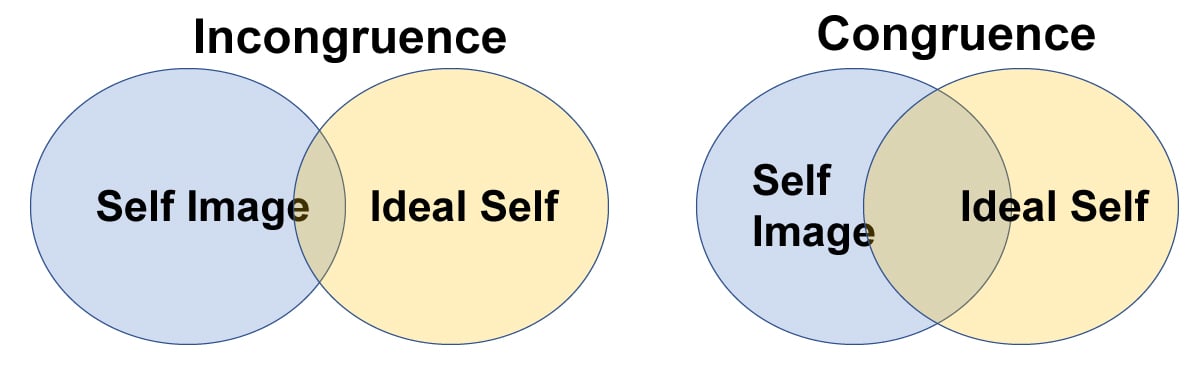

Rogers (1959) explained that individuals strive to experience life and behave in ways that align closely with their self-image (how they currently view themselves) and their ideal-self (who they aspire to become).

The greater the alignment or congruence between these two perceptions, the higher the individual’s self-worth and psychological health.

Conversely, when a discrepancy arises between self-image and ideal-self, a state of incongruence occurs. Rogers believed incongruence typically originates from internalizing external conditions of worth, often imposed during childhood.

As individuals deviate from fully accepting and integrating all their authentic experiences into their self-concept, their sense of being a unified and whole person diminishes.

Consequently, various aspects of the self may feel threatened or distorted by specific experiences, contributing to psychological distress.

The humanistic approach emphasizes that each person’s self-concept is uniquely personal, comprising three primary components:

- Self-worth Self-worth (or self-esteem) refers to how individuals value themselves. Rogers emphasized that feelings of self-worth emerge early in life, shaped significantly by interactions with parents and caregivers during childhood.

- Self-image Self-image pertains to how individuals perceive themselves, which strongly influences psychological well-being. This perception includes both physical appearance (body image) and inner personal characteristics. An individual’s self-image profoundly affects their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, influencing their overall mental health and functioning in daily life.

- Ideal-self The ideal-self represents the aspirations, ambitions, and the person one strives to become. This component is inherently dynamic and evolves continually throughout different life stages, reflecting changing goals, values, and experiences as individuals grow and mature.

Therapy

Client-centered therapy, pioneered by Carl Rogers, is extensively utilized in various fields, including healthcare, social work, and corporate settings.

This therapeutic approach significantly improves individuals’ quality of life by enabling them to address and overcome personal and emotional challenges.

Central to humanistic therapies is the belief that psychological difficulties often arise from self-deception or incongruence between one’s self-image and ideal self.

Humanistic therapists aim to help clients develop greater insight, accurate self-perception, and self-acceptance.

The primary goal of humanistic therapies, such as client-centered and Gestalt therapies, is to facilitate personal growth and enable individuals to achieve their fullest potential.

Client-centered therapy specifically seeks to enhance clients’ self-worth and reduce the gap between their actual self-concept and their ideal self.

This therapy is characterized as non-directive, empowering clients to explore and find their own solutions within a supportive, accepting environment that offers unconditional positive regard.

Unlike psychoanalysis, which frequently emphasizes past experiences, client-centered therapy places a strong emphasis on present experiences and current self-perceptions.

Education

In education, Carl Rogers viewed traditional schools as rigid and resistant to meaningful change.

He advocated for a ‘student-centered learning’ approach, encouraging learners to actively participate in setting their learning agendas and goals.

He was critical of traditional testing methods, asserting: “I believe that the testing of the student’s achievements in order to see if he meets some criterion held by the teacher, is directly contrary to the implications of therapy for significant learning.”

Humanistic educational philosophies have inspired the establishment of open classrooms, where students have greater autonomy over their educational experiences.

They are free to decide what and how they study, with teachers acting primarily as facilitators who support students’ individual learning paths.

An illustrative example of humanistic education in practice is the Summerhill School in the UK, founded by A.S. Neill.

At Summerhill, students benefit from a clear yet flexible structure where they have the freedom to choose subjects and learning materials.

This environment promotes creativity, self-direction, responsibility, and tolerance among students, demonstrating the practical effectiveness of applying humanistic principles in education.

Critical Evaluation

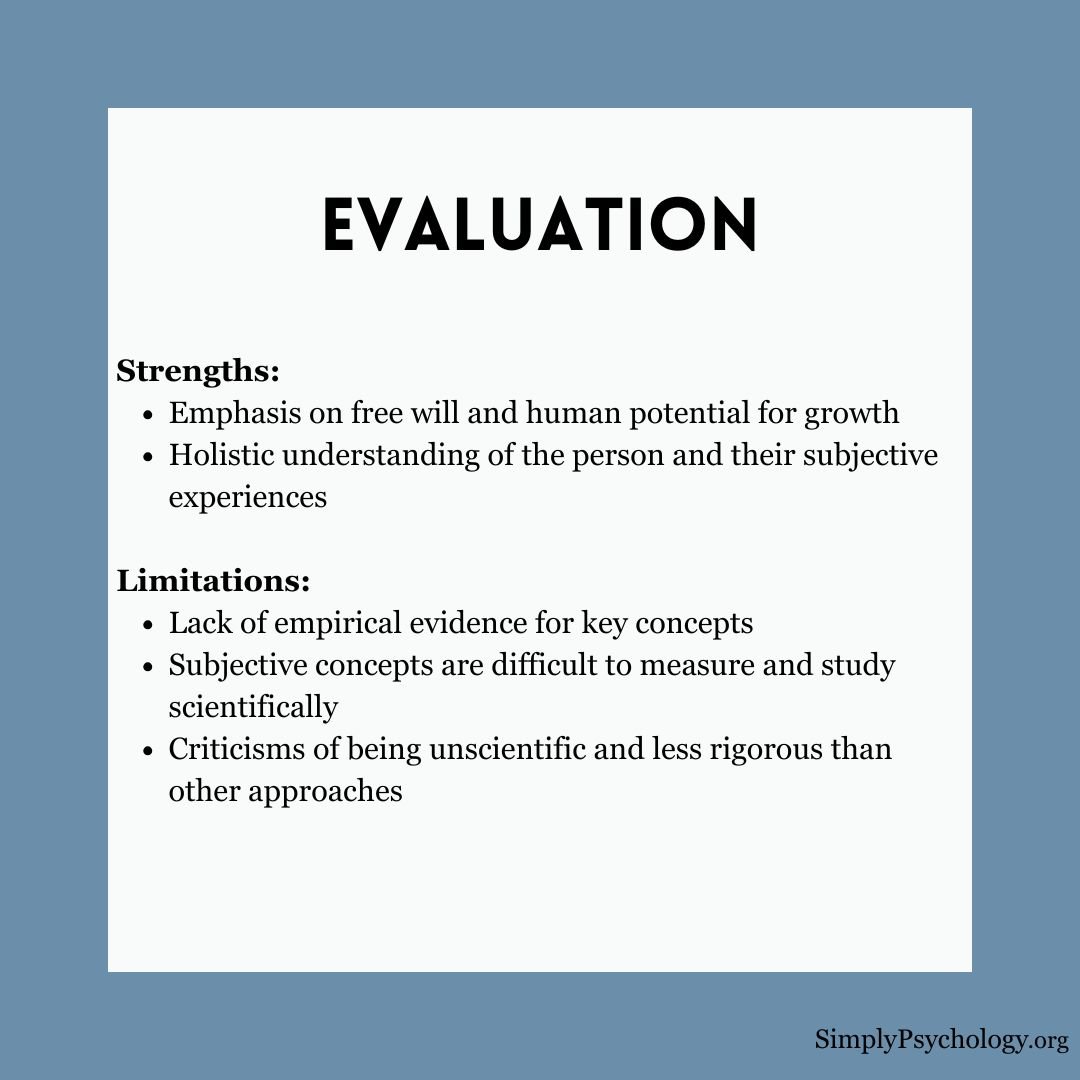

Strengths

Humanistic psychology takes a holistic approach, emphasizing the integration of emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual aspects of the individual.

Unlike reductionist approaches such as behaviorism, which isolates behavior into stimulus-response units, or psychoanalysis, which focuses mainly on unconscious drives, humanistic psychology sees the person as a whole.

This is reflected in therapeutic methods like person-centered therapy, which explore the client’s experience from multiple dimensions -emotions, thoughts, relationships, and self-concept – rather than treating symptoms in isolation.

This aligns with Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs, which considers multiple levels of human motivation.

This holistic emphasis results in a positive consequence: it allows therapists and practitioners to tailor interventions more personally and compassionately, increasing client engagement and satisfaction.

It also broadens psychology’s focus beyond illness, promoting wellbeing and personal fulfillment.

However, it may lack precision in diagnosing and treating specific mental disorders due to its broad scope.

The humanistic approach places significant value on personal agency, free will, and the human capacity for growth.

Humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow emphasized that individuals are not passive products of their environment or unconscious drives but active agents capable of self-determination and change.

This is central to theories such as Rogers’ concept of the actualizing tendency, the innate drive toward growth, fulfillment, and psychological congruence.

This yields a positive consequence: it fosters empowerment and optimism in therapeutic settings, helping clients take control of their lives and foster resilience.

It also supports progressive views in education and counseling by promoting autonomy and intrinsic motivation.

However, it may oversimplify the complexity of human motivation by underplaying structural, social, and unconscious influences.

Humanistic psychology has had practical success in therapeutic settings, particularly through client-centered therapy.

Client-centered therapy, developed by Carl Rogers, relies on creating a non-judgmental, empathetic, and accepting environment where clients feel safe to explore their feelings and beliefs.

Research suggests that the therapeutic relationship is a major factor in positive outcomes, and humanistic therapy’s emphasis on unconditional positive regard and empathy directly supports this.

The positive consequence is that this approach has demonstrably improved therapeutic rapport and client outcomes in cases involving self-esteem, anxiety, and identity crises.

However, its less structured nature can limit its utility for more severe mental health conditions requiring directive or symptom-focused intervention.

One significant strength of humanistic psychology is its influential impact on modern therapeutic practices.

Humanistic psychology emphasizes individual autonomy, self-awareness, and personal empowerment.

By advocating for client-centered approaches, this perspective has reshaped therapy into a collaborative process, significantly reducing the stigma surrounding mental health treatments.

Clients are now viewed as active participants in their recovery rather than passive recipients of treatment.

As a result, therapeutic practices today prioritize giving clients greater control and involvement in their treatment plans, promoting openness and acceptance, and leading to more personalized and effective outcomes.

Limitations

A major criticism of humanistic psychology is its lack of empirical rigor and scientific credibility.

Humanistic concepts such as self-actualization, congruence, and the actualizing tendency are deeply subjective and difficult to operationalize or measure.

While Rogers attempted to bring some objectivity through tools like the Q-sort, the field largely relies on introspective and qualitative methods like case studies and self-reports, which are not easily replicable or falsifiable – criteria essential for scientific validation.

This has negative consequences: it undermines the approach’s credibility within academic psychology and limits its integration into evidence-based practice.

Consequently, funding, research, and institutional support for humanistic methods remain limited compared to cognitive-behavioral approaches that emphasize measurable outcomes.

Humanistic psychology has been criticized for ethnocentrism, as it promotes values aligned primarily with Western, individualistic cultures.

Core principles of the approach – such as autonomy, individual fulfillment, and self-actualization—are deeply rooted in Western ideologies.

In collectivist cultures, where interdependence, social harmony, and familial duty are more central, the emphasis on the individual’s personal growth may seem alien or even selfish.

This has negative implications: the effectiveness of humanistic therapy may diminish in non-Western contexts, making it less applicable on a global scale.

It also raises ethical concerns about imposing culturally biased models of mental health, suggesting that a more culturally adaptive or emic approach may be necessary.

The approach is often criticized as overly idealistic and may not adequately account for destructive human behaviors.

Humanistic psychology assumes an inherently positive view of human nature – that people strive toward growth and fulfillment.

However, this outlook struggles to explain or address behaviors driven by aggression, cruelty, or pathology.

Events like genocide, abuse, and chronic criminal behavior challenge the assumption that humans naturally gravitate toward goodness.

This produces negative consequences: it can render the approach naïve or insufficient when dealing with darker aspects of human psychology, potentially leading to therapeutic blind spots.

It may also neglect the need for confronting or managing harmful behaviors directly, particularly in forensic or high-risk clinical settings.

Humanistic therapy is often less effective for treating severe psychological disorders.

While effective for personal growth and moderate psychological issues, the non-directive nature of humanistic therapy makes it less suited to severe conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or chronic depression.

These disorders often require structured, evidence-based interventions such as medication or cognitive-behavioral techniques, which directly target symptoms and cognitive distortions.

The negative outcome is that humanistic therapy has limited utility in clinical settings where symptom reduction and behavioral management are essential.

This confines its relevance mostly to milder conditions, coaching, or supportive counseling, limiting its application in mainstream clinical psychology.

Issues and Debates

Free will vs. Determinism

Humanistic psychology uniquely emphasizes the concept of free will, suggesting individuals have the autonomy and capability to make conscious choices that shape their lives.

However, this stance is nuanced. On one hand, it strongly advocates for human freedom and personal agency.

Yet, on the other hand, it recognizes that external influences, particularly how others treat us and whether we receive unconditional positive regard and respect, significantly affect our behavior and self-perception.

Thus, the humanistic approach presents a balanced view, integrating personal autonomy with external influences.

Nature vs. Nurture

The humanistic approach acknowledges the interactive roles of both nature and nurture in shaping human behavior and experiences.

It recognizes the innate biological drives and psychological needs highlighted by Maslow’s hierarchy (nature), as well as the profound impact of personal experiences and the environment in shaping perception, behavior, and self-concept (nurture).

Holism vs. Reductionism

Humanistic psychology is fundamentally holistic.

It focuses on understanding individuals as whole, integrated beings rather than breaking down human behavior into smaller, isolated components.

This holistic approach maintains that behaviors, experiences, and perceptions must be viewed within the broader context of the individual’s life and environment.

Idiographic vs. Nomothetic

The humanistic approach is idiographic, emphasizing the uniqueness of each individual rather than seeking to establish universal laws that apply broadly across populations.

Humanistic psychology values personalized exploration of experiences, behaviors, and motivations, aiming to understand the distinct qualities that define each person’s individual journey.

Are the research methods used scientific?

Due to its emphasis on individual uniqueness and subjective experience, the humanistic approach typically avoids traditional scientific methodologies, which rely on standardized measurement and quantification.

Instead, it favors qualitative methods such as personal narratives, case studies, and open-ended interviews, believing these approaches more effectively capture the complexity and depth of human experiences.

References

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-96.

Rogers, C. R. (1946). Significant aspects of client-centered therapy. American Psychologist, 1, 415-422.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being (2nd ed.). New York: D. Van Nostrand.

Rogers, C. R. (1946). Significant aspects of client-centered therapy. American Psychologist 1, 415-422.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In (ed.) S. Koch, Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the person and the social context. New York: McGraw Hill.