The Little Albert Experiment by Watson and Rayner tested whether an infant could be classically conditioned to fear a neutral stimulus.

By pairing a white rat with a loud noise, they induced fear that later generalized to similar furry objects, demonstrating learned emotional responses – but raising major ethical concerns by today’s standards.

Key Takeaways

- Aim: A 1920 study by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner aimed to test whether a human infant could learn fear through classical conditioning.

- Method: A white rat was paired several times with a loud, startling noise until 9-month-old Little Albert showed fear of the rat even without the noise.

- Findings: The fear extended to other furry objects – such as a rabbit, a dog, a fur coat, and a Santa Claus mask – demonstrating stimulus generalization.

- Applications: The experiment became a classic teaching example for understanding how phobias might develop and for illustrating principles of classical conditioning.

- Criticism: Later reviews noted methodological weaknesses and raised ethical concerns, including the lack of informed consent and failure to reverse the induced fear.

Little Albert Experiment

-

Can an infant be conditioned to fear an animal that appears simultaneously with a loud, fear-arousing sound?

-

Would such fear transfer to other animals or inanimate objects?

-

How long would such fears persist?

Ivan Pavlov showed that classical conditioning applied to animals. Did it also apply to humans? In a famous (though ethically dubious) experiment, John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner showed it did.

Conducted at Johns Hopkins University between 1919 and 1920, the experiment aimed to provide experimental evidence for the conditioning of emotional responses in infants.

At the outset, Watson and Rayner worked with a healthy, fearless nine-month-old boy they nicknamed Little Albert.

His exact identity remains uncertain, with researchers debating whether he was Albert Barger or Douglas Merritte.

The researchers obtained permission from Albert’s mother to observe and test him, designing a procedure to see if they could condition a fear response to a previously neutral object.

Participant

Little Albert had been raised from birth in a hospital environment, as his mother worked as a wet nurse at the Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children.

At nine months old, he was healthy, weighing twenty-one pounds, and was described by Watson and Rayner as “stolid and unemotional.”

This unusually calm temperament, along with his robust health, was one of the main reasons he was chosen as the subject for the study.

This very stability may also have shaped how he responded during the conditioning trials, making him less reactive than a more emotionally expressive child might have been.

Baseline Session

When Albert was approximately nine months old, the researchers tested his reactions to various neutral stimuli.

He showed no fear of a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, masks (with and without hair), cotton wool, or burning newspapers.

Instead, he typically tried to reach out and manipulate the objects — curious rather than afraid.

The only thing that startled him was the sudden striking of a steel bar behind his head, which caused him to startle and briefly hold his breath.

On the second strike, his lips trembled, and on the third, he cried suddenly. This was the first time a laboratory situation had produced fear in him.

Observations from his mother and hospital staff confirmed that Albert rarely cried and had never shown fear or rage before.

Conditioning Sessions

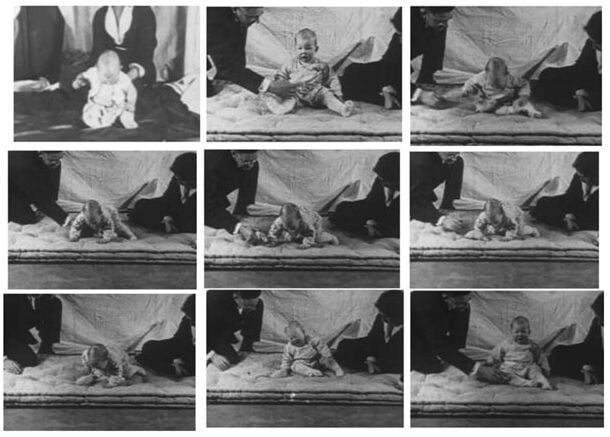

Two months later, when Albert was just over 11 months old, Watson and Rayner began the conditioning procedure.

Their aim was to see if they could make him fear a white rat by pairing it with the loud noise that had previously startled him.

First session (11 months, 3 days):

When the rat was placed near Albert, he reached for it with interest. Just as his hand touched the animal, the steel bar was struck behind his head.

He jumped violently, buried his face in the mattress, but did not cry.

On the second pairing, he again reached for the rat, but when the noise sounded he started violently and whimpered. The researchers stopped after these two trials so as not to upset him too much.

Second session (11 months, 10 days):

A week later, Albert was tested again. At first, when shown the rat alone, he fixated on it but hesitated to touch.

When it brushed his hand, he pulled away sharply. After several more pairings of rat and noise (five in total), his reaction escalated: when the rat was presented without any sound, he puckered his face, whimpered, turned away, and eventually began to cry.

On one occasion, he crawled away so rapidly he nearly fell from the table.

By the end of the second conditioning session, when Albert was shown the rat, he reportedly cried and “began to crawl away so rapidly that he was caught with difficulty before reaching the edge of the table” (p. 5). Watson and Rayner interpreted these reactions as evidence of fear conditioning.

Between trials, Watson and Rayner gave him his wooden blocks to play with. This was an important control: it showed that his fear was specific to the rat, not a generalized anxiety.

With the blocks, Albert played happily, smiling and gurgling, which helped him calm down between the stressful pairings.

By the end of the second session, Watson and Rayner concluded that Albert had developed a conditioned emotional reaction: the once-neutral rat now triggered fear responses even without the loud noise.

Transfer Sessions

After Albert’s fear of the rat had been established, Watson and Rayner tested whether it would extend to other animals and objects.

This was an important question: could a conditioned fear generalize to stimuli that were similar in appearance or texture?

Reactions to animals

-

Rabbit: Albert leaned away, whimpered, and eventually burst into tears when it touched him.

-

Dog: Initially a milder reaction — shrinking back without crying — but when the dog approached his face, Albert turned away, whimpered, and began to cry.

Reactions to objects

-

Fur coat: He withdrew sharply to the side, cried, and tried to crawl away.

-

Cotton wool: He kicked it away and refused to touch it with his hands, though he eventually played with the paper wrapper while avoiding direct contact.

-

Santa Claus mask and human hair: The mask with white hair made him cry and attempt to turn away. Similarly, Watson’s own hair and that of two observers provoked negative reactions.

Conflicting responses

In some cases, he displayed a “conflicting tendency to manipulate” the objects — reaching out to touch but quickly withdrawing.

At other times, he played more vigorously with his wooden blocks after a frightening trial, almost as if compensating for the fear by slamming them down harder than before.

Testing in a new environment

The researchers also tested Albert in a new environment — a large, well-lit lecture hall instead of the small dark room where previous trials had taken place.

In this setting, some of his reactions were weaker.

For example, his response to the rabbit and rat was less intense, but when a previously quiet dog suddenly barked near his face, Albert fell over and cried loudly, startling even the adult observers.

These tests showed that Albert’s conditioned fear could generalize widely to other furry objects, though his reactions varied in strength depending on the stimulus and setting.

Experimental Procedure

| Session | Age | Stimuli Shown |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 months & 26 days | Baseline: rat, rabbit, dog, monkey, masks, cotton wool, burning newspapers (no fear). Loud noise test: startle → lip tremble → crying. |

| 2 | 11 months & 3 days | Conditioning: Rat + loud noise (2 pairings). Startle/whimper. Wooden blocks given between trials to maintain a neutral emotional state. |

| 3 | 11 months & 10 days | Conditioning: Test with rat alone (elicited mild fear). Rat paired with loud noise (5 pairings). Test with rat alone (elicited strong fear). |

| 4 | 11 months & 15 days | Transfer: Rat, rabbit, dog, fur coat, cotton wool, hair, Santa mask. Fear to most stimuli; some manipulation attempts. |

| 5 | 11 months & 20 days | Transfer: In original room: tests with rat, rabbit, and dog; extra rat conditioning; and first direct conditioning of rabbit and dog with noise. In new room: tests with same animals; extra rat conditioning; barking dog incident startled both Albert and adult observers. |

| 6 | 12 months, 21 days | Transfer (one-month follow-up): Santa mask, fur coat, rat, rabbit, and dog. Some weaker reactions (partial extinction), but avoidance persisted. New behaviors included head nodding, shuddering, and thumb-sucking (blocked fear until removed). Albert discharged after this session — no deconditioning attempted. |

Classical Conditioning

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): This is a stimulus that, before conditioning, does not naturally bring about the response of interest. In this case, the Neutral Stimulus was the white laboratory rat. Initially, Little Albert had no fear of the rat, he was interested in the rat and wanted to play with it.

- Unconditioned Stimulus (US): A stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without learning. In the experiment, the unconditioned stimulus was the loud, frightening noise, made by striking a steel bar with a hammer behind Albert’s head.

- Unconditioned Response (UR): The unlearned, natural reaction to the unconditioned stimulus. In this case, the Unconditioned Response was Albert’s fear response to the loud noise – crying and showing distress.

- Conditioning Process: Watson and Rayner paired the rat (NS) with the loud noise (US). Each time Albert reached for or looked at the rat, the steel bar was struck. After several pairings, Albert began to associate the rat with the frightening noise.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): After several pairings, the previously Neutral Stimulus (the rat) becomes the conditioned stimulus, as it now elicits the fear response even without the presence of the loud noise.

- Conditioned Response (CR): The learned reaction to the conditioned stimulus. The Conditioned Response was Albert’s fear of the rat. Even without the loud noise, he became upset and showed signs of fear whenever he saw the rat.

One-Month Follow-Up

Thirty-one days later, Albert’s fear responses were retested. Some were weaker than before, showing signs of partial extinction, but clear avoidance remained.

It also revealed how children may use coping mechanisms, like thumb-sucking, to manage distress.

Persistence of fear

When shown the rat and rabbit, Albert no longer reacted with immediate, intense crying, but he still withdrew his body, turned his head away, and avoided direct contact.

His reactions suggested that the conditioned fear had diminished in intensity, but not disappeared.

New behaviors

During this follow-up, Albert displayed several new fear-related behaviors:

-

Head nodding: a repetitive motion when distressed.

-

Shuddering: a physical tremor-like response.

-

Covering his face: using his hands to shield himself from the stimulus.

Ambivalence with the rabbit

When presented with the rabbit, Albert alternated between curiosity and avoidance.

At times he reached out tentatively to touch it, but then quickly withdrew in distress.

On one occasion, he vocalized “da da” while leaning away, reflecting a mix of social engagement and fear.

Thumb-sucking as a coping strategy

Albert sometimes sucked his thumb during testing.

This behavior seemed to block or soothe his fear response, making him appear calm.

Watson and Rayner had to physically remove his thumb from his mouth in order to elicit the conditioned reactions again.

Extinction and Generalization of Fear

In this experiment, a baby who had previously shown no fear of a white rat was conditioned to become afraid of it.

The study also illustrated two important concepts from Pavlov’s work on classical conditioning.

- Extinction occurs when a conditioned association gradually weakens and eventually disappears if it is not reinforced. Although the conditioned fear response can be strong at first, repeated exposure to the conditioned stimulus without the unconditioned stimulus will cause the reaction to fade.

- Generalization happens when a conditioned response transfers to stimuli similar to the original one. For Albert, fear extended beyond the rat to other furry objects such as a rabbit, dog, fur coat, cotton wool, and even a Santa Claus mask.

Even after a month, Albert still avoided the rat and rabbit, though his reactions were less intense. This showed that extinction was underway but incomplete.

Importantly, Watson and Rayner noted that the conditioned fear could be quickly renewed by repeating the original rat-and-noise pairing, suggesting that once learned, emotional associations can be difficult to fully erase.

Planned Deconditioning

The study ended suddenly when Albert’s mother withdrew him from the hospital on the same day as the last tests.

As a result, Watson and Rayner were unable to carry out their planned deconditioning procedures to remove the learned fear, leaving Albert’s emotional state unresolved.

Watson and Rayner intended to explore methods for removing conditioned fear but were unable to do so when Albert left the hospital. They outlined four strategies they would have tried:

- Habituation: Repeated exposure to the feared stimulus (such as the rat) without the noise, until the fear response gradually diminished. This is similar to what modern psychologists call exposure therapy.

- Tactile reconditioning: Pairing the feared object with pleasant tactile stimulation of “erogenous zones” (such as the lips or nipples). By today’s standards, this method seems ethically troubling, but at the time Watson believed it could create competing positive associations to counteract fear.

- Feeding association: Presenting the feared object while giving Albert food, with the aim of creating a positive emotional link between the two. This approach reflects the principle that strong biological drives, such as hunger, can override fear responses.

- Constructive play: Encouraging Albert to manipulate or play with the feared object, possibly by modeling the behavior and prompting him to imitate. The idea was that positive interaction could gradually reduce avoidance.

Critical Evaluation

Methodological Limitations

The study is often cited as evidence that phobias can develop through classical conditioning. However, critics have questioned whether conditioning actually occurred due to methodological flaws (Powell & Schmaltz, 2022).

The study did not control for pseudoconditioning, meaning the results might not reflect true classical conditioning.

Pseudoconditioning occurs when a subject becomes generally more fearful or reactive to stimuli simply because of repeated exposure to a startling event, rather than forming a specific association between two stimuli.

In Albert’s case, repeated exposure to the loud noise could have made him more wary of any new object, regardless of whether it had been paired with the noise.

This weakens the claim that the white rat specifically caused the fear response. If Albert’s reactions were due to general sensitization, the experiment would not be strong evidence for the conditioning of phobias in humans.

The study failed to control for maturation, making it unclear whether age-related changes influenced Albert’s reactions.

Albert was 11 months old at the start of conditioning and 12 months by the final test.

Developmental psychology shows that fear responses can naturally emerge as infants grow and become more aware of their surroundings.

Without a control group or baseline over time, it’s impossible to rule out that his increased fearfulness was a normal part of development.

If maturation contributed to Albert’s behavior, the results cannot be attributed solely to the conditioning procedure, reducing the study’s validity.

Albert’s reactions were inconsistent, and the conditioned fear appeared weak in later sessions.

The historical record and film analysis show that Albert sometimes interacted with the rat without clear distress and reacted only mildly to other furry stimuli.

These inconsistencies suggest that the conditioning was not robust or long-lasting.

Weak and variable responses limit the study’s usefulness in demonstrating how strong or persistent conditioned fears can be, making the findings less applicable to real-world phobias.

The experimental design confounded conditioning and generalization.

Watson and Rayner used the same stimuli for conditioning and for testing generalization.

For example, the rabbit and dog were both conditioned with noise and later tested as generalized stimuli.

This means it’s unclear whether fear responses to these animals were due to generalization from the rat or direct conditioning.

This reduces the clarity of the results, making it harder to draw firm conclusions about the mechanisms of generalization in humans.

Other methodological criticisms include:

Was It Really a Phobia?

Some psychologists question whether Albert ever developed a genuine phobia.

His fear responses were inconsistent and often weak.

For example, when allowed to suck his thumb, Albert showed no fear at all – even during conditioning.

This thumb-sucking appeared to block his distress, and Watson had to physically remove his thumb more than 30 times before a fear response could be observed.

Lack of Control and Measurement

The study did not include a control subject for comparison, making it impossible to rule out alternative explanations for Albert’s reactions.

In addition, the researchers did not objectively measure his fear.

They relied on descriptive notes rather than clear operational definitions of behavior, which weakens the reliability of the findings.

Problems of Generalization

The experiment was conducted on a single infant, which means the results cannot be generalized to other children.

Albert was also unusual: he had been reared in a hospital environment since birth and was described by staff as never having shown fear or rage.

His temperament may have made him a poor representative of typical infant development.

Theoretical Limitations

The study ignored the role of cognitive processes in fear responses.

The behavioral model underlying the experiment focuses on observable stimulus–response links, but phobias also involve cognitive elements such as irrational beliefs or selective attention.

Later research, such as Tomarken et al. (1989), showed that phobic individuals tend to overestimate the presence of feared stimuli.

Tomarken et al. (1989) presented a series of slides of snakes and neutral images (e.g., trees) to phobic and non-phobic participants.

The phobics tended to overestimate the number of snake images presented.

By excluding cognitive processes, the study presents an incomplete explanation of phobia development, limiting its theoretical relevance in modern psychology.

The Little Albert Film

Powell and Schmaltz (2022) examined film footage of the study for evidence of conditioning. Clips showed Albert’s reactions during baseline and final transfer tests but not the conditioning trials. Analysis of his reactions did not provide strong evidence of conditioning:

- With the rat, Albert was initially indifferent and tried to crawl over it. He only cried when the rat was placed on his hand, likely just startled.

- With the rabbit, dog, fur coat, and mask, his reactions could be explained by being startled, innate wariness of looming objects, and other factors. Reactions were inconsistent and mild.

Overall, Albert’s reactions seem well within the normal range for an infant and can be readily explained without conditioning. The footage provides little evidence he acquired conditioned fear.

The belief the film shows conditioning may stem from:

- Viewer expectation – titles state conditioning occurred and viewers expect to see it.

- A tendency to perceive stronger evidence of conditioning than actually exists.

- An ongoing perception of behaviorism as manipulative, making Watson’s conditioning of a “helpless” infant seem plausible.

Rather than an accurate depiction, the film may have been a promotional device for Watson’s research. He hoped to use it to attract funding for a facility to closely study child development.

This could explain anomalies like the lack of conditioning trials and rearrangement of test clips.

Ethical Issues

The Little Albert Experiment was conducted in 1920 before ethical guidelines were established for human experiments in psychology.

When judged by today’s standards, the study has several concerning ethical issues:

- Lack of Informed Consent: Albert’s mother was not fully informed about the true aims of the study. She did not know that her child would be deliberately frightened. This absence of transparency violated the principle of respect for persons and denied her the opportunity to make an informed choice.

- Deliberate Psychological Harm: Watson and Rayner intentionally induced fear in an infant. From the perspective of nonmaleficence (“do no harm”), this was highly unethical. The distress Albert displayed—crying, withdrawal, and attempts to escape—shows that the procedure caused clear emotional suffering.

- Failure to Decondition: The researchers ended the study without attempting to reverse the conditioned fear. By failing to provide deconditioning, they neglected the principle of beneficence—the duty to minimize harm and maximize well-being. Albert was left in a fearful state with no effort to restore his emotional balance.

- Possible Long-Term Effects: Because Albert was withdrawn from the hospital after the final tests, no follow-up was ever conducted. This raises the troubling possibility that he carried the induced fears into later development. Watson’s decision not to track Albert’s wellbeing illustrates a disregard for responsibility to participants.

Learning Check

- Summarise the process of classical conditioning in Watson and Rayner’s study.

- Explain how Watson and Rayner’s methodology is an improvement on Pavlov’s.

- What happened during the transfer sessions? What did this demonstrate?

- Why is Albert’s reaction to similar furry objects important for the interpretation of the study?

- Comment on the ethics of Watson and Rayner’s study.

- Support the claim that in ignoring the internal processes of the human mind, behaviorism reduces people to mindless automata (robots).

References

Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’s

infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 64, 605–614.

Digdon, N., Powell, R. A., & Harris, B. (2014). Little Albert’s alleged neurological persist impairment: Watson, Rayner, and historical revision. History of Psychology, 17, 312–324.

Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. (2012). Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child. History of Psychology, 15, 1–34.

Griggs, R. A. (2015). Psychology’s lost boy: Will the real Little Albert please stand up? Teaching of Psychology, 42, 14–18.

Harris, B. (1979). Whatever happened to little Albert?. American Psychologist, 34(2), 151.

Harris, B. (2011). Letting go of Little Albert: Disciplinary memory, history, and the uses of myth. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 47, 1–17.

Harris, B. (2020). Journals, referees and gatekeepers in the dispute over Little Albert, 2009–2014. History of Psychology, 23, 103–121.

Powell, R. A., Digdon, N., Harris, B., & Smithson, C. (2014). Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as “psychology’s lost boy.” American Psychologist, 69, 600–611.

Powell, R. A., & Schmaltz, R. M. (2021). Did Little Albert actually acquire a conditioned fear of furry animals? What the film evidence tells us. History of Psychology, 24(2), 164.

Todd, J. T. (1994). What psychology has to say about John B. Watson: Classical behaviorism in psychology textbooks. In J. T. Todd & E. K. Morris (Eds.), Modern perspectives on John B. Watson and classical behaviorism (pp. 74–107). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Tomarken, A. J., Mineka, S., & Cook, M. (1989). Fear-relevant selective associations and covariation bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98 (4), 381.

Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review, 20, 158-177.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 (1), 1.

Watson, J. B., & Watson, R. R. (1928). Psychological care of infant and child. New York, NY: Norton.

Further Information

- Finding Little Albert

- Mystery solved: We now know what happened to Little Albert

- Psychology’s lost boy: Will the real Little Albert please stand up?

- Journals, referees, and gatekeepers in the dispute over Little Albert, 2009-2014

- Griggs, R. A. (2014). The continuing saga of Little Albert in introductory psychology textbooks. Teaching of Psychology, 41(4), 309-317.