The Strange Situation Experiment is a study by psychologist Mary Ainsworth that measures how infants respond to separations and reunions with their caregiver. It helps identify different attachment styles, like secure, avoidant, or anxious, based on how the child reacts when the caregiver leaves and returns.

Key Takeaways

- The strange situation is a standardized procedure devised by Mary Ainsworth in the 1970s to observe attachment security in children within the context of caregiver relationships.

- It applies to infants between the age of nine and 18 months.

- The procedure involves a series of eight episodes lasting approximately 3 minutes each, whereby a mother, child, and stranger are introduced, separated, and reunited.

How do I reference the strange situation?

Both references are frequently cited in scholarly works on attachment theory.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

This seminal book is the primary academic source describing the Strange Situation methodology, results, and the classification of attachment styles.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127388

This 1970 article is crucial as it was one of the first detailed publications introducing the Strange Situation procedure to the academic community.

Background

The Strange Situation is a structured observational method developed by psychologist Mary Ainsworth to measure how securely an infant is attached to their caregiver.

Initially, Ainsworth observed infant behavior naturally within their homes.

In her early studies in Uganda (Africa), infants clearly demonstrated attachment behaviors, like using their mothers as a safe base from which to explore and showing visible distress when separated or encountering strangers.

However, later studies conducted in Baltimore showed that American babies were less clearly demonstrating these behaviors, likely because their familiar home environments didn’t trigger attachment behaviors as intensely.

Recognizing this, Ainsworth developed a controlled, yet slightly unfamiliar scenario designed to reliably activate infants’ natural attachment behaviors.

This became known as the Strange Situation.

It created intensified versions of common situations, including brief separations from caregivers, interactions with a stranger, and reunions with caregivers, to vividly illustrate attachment styles.

The Strange Situation provides insight into a child’s expectations about their caregiver’s availability, essentially how secure they feel based on previous interactions.

It’s often described as a “laboratory microcosm,” a simplified environment allowing researchers to clearly observe the balance infants strike between their attachment needs (comfort and safety) and their desire to explore the environment around them.

Strange Situation Procedure

The security of attachment in one- to two-year-olds was investigated using the strange situation paradigm in order to determine the nature of attachment behaviors and styles of attachment.

Ainsworth and Bell (1970) conducted a controlled observation recording the reactions of a child and mother (caregiver), who were introduced to a strange room with toys.

About 100 middle-class American infants and their mothers participated in the strange situation.

The strange situation procedure was designed to be novel enough to elicit exploratory behavior and yet not so strange that it would evoke fear and heighten attachment behavior at the outset.

The room was set up with a clear 9 x 9-foot floor space divided into 16 squares for recording location and movement.

One end housed a chair laden with toys, while the other had chairs for the mother and a stranger. The baby was placed centrally, free to move around. The mother and stranger were pre-instructed on their roles.

The child is observed playing for 20 minutes while caregivers and strangers enter and leave the room, recreating the flow of the familiar and unfamiliar presence in most children’s lives.

Ainsworth & Bell observed from the other side of a one-way mirror, so the children did not know they were being observed.

The infant’s behavior was observed during eight pre-determined ‘episodes’ of approximately 3 minutes each.

Episode 1: Mother, Baby, and Experimenter

-

Who is present: Mother, baby, and experimenter.

-

Duration: Less than one minute.

-

Purpose: Introduction of the infant and mother to the testing environment, allowing brief settling-in.

- Description: The mother places the baby in a specific location and sits quietly, responding only if the baby seeks attention.

-

Behaviors observed: Exploratory Behavior: Observers briefly noted initial behaviors like exploring the environment and initial responses to the experimenter.

-

Categories: Proximity and contact seeking.

Episode 2: Mother and Baby Alone

-

Who is present: Mother and baby.

-

Duration: Three minutes.

-

Purpose: Observe the baby’s exploratory behavior and interactions in an unfamiliar environment while the mother is present.

-

Description: The stranger enters, sits silently for one minute, converses with the mother for another minute, and then gradually approaches the baby with a toy, At the end of this episode, the mother quietly exits the room.

-

Behaviors observed: Observers assessed how comfortably the baby explored and interacted with toys, and how effectively the baby used the mother as a secure base.

-

Categories: Proximity and contact seeking, Contact maintaining.

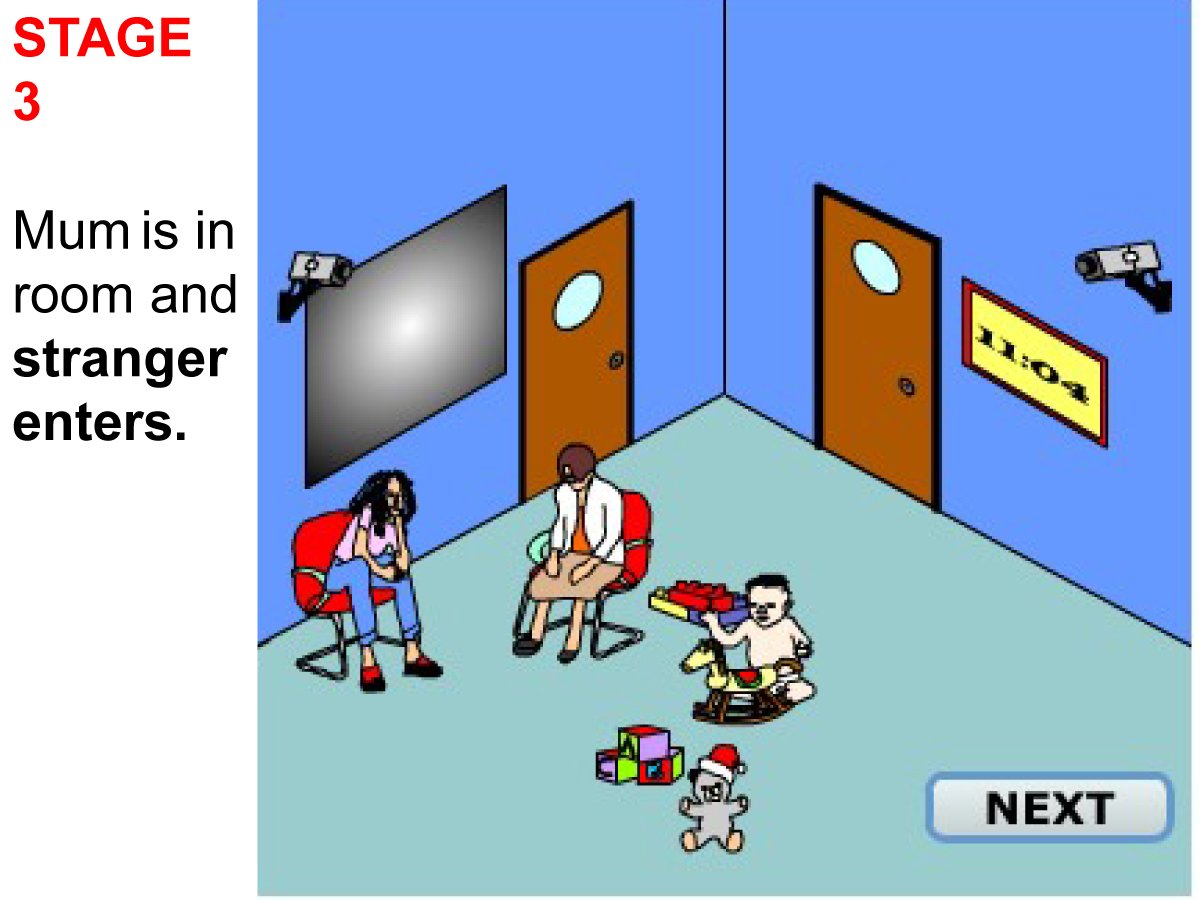

Episode 3: Stranger Joins Mother and Infant

-

Who is present: Mother, baby, and stranger.

-

Duration: Three minutes.

-

Purpose: Assess the infant’s response to the presence of a stranger while the mother is still present.

-

Description: The stranger enters, sits silently for one minute, converses with the mother for another minute, and then gradually approaches the baby with a toy. At the end of this episode, the mother quietly exits the room.

-

Behaviors observed: Observers noted how the baby’s exploration and comfort level changed with the introduction of a stranger and how the baby sought or avoided comfort and interaction.

-

Categories: Proximity and contact seeking, Avoidance of proximity and contact, Resistance to contact and comfort.

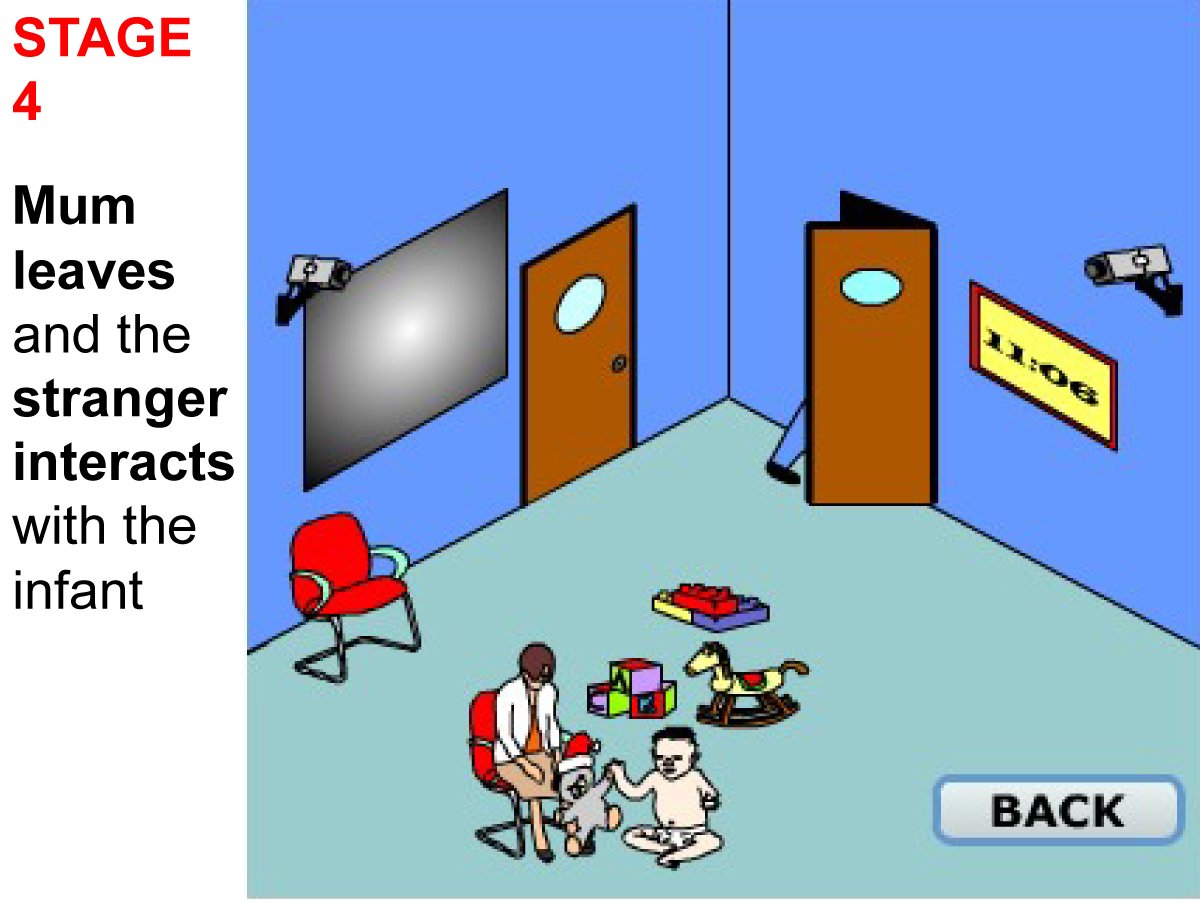

Episode 4: Mother Leaves Baby and Stranger Alone

-

Who is present: Baby and stranger.

-

Duration: Up to three minutes, shorter if infant distress is significant.

-

Purpose: Measure the infant’s separation anxiety and their response to comfort attempts by a stranger without the mother present.

-

Description: Researchers note signs of distress (crying, searching, reduced exploration) or comfort (calm engagement).

If the baby is content, the stranger observes without interference. If inactive, the stranger gently engages the infant. If distressed, the stranger attempts comfort. The episode ends early if distress cannot be soothed.

-

Behaviors observed: Observers documented the baby’s immediate reactions, including distress signals, efforts to find the mother, and responses to the stranger’s attempts to provide comfort.

-

Categories: Search behavior, Avoidance of proximity and contact, Resistance to contact and comfort.

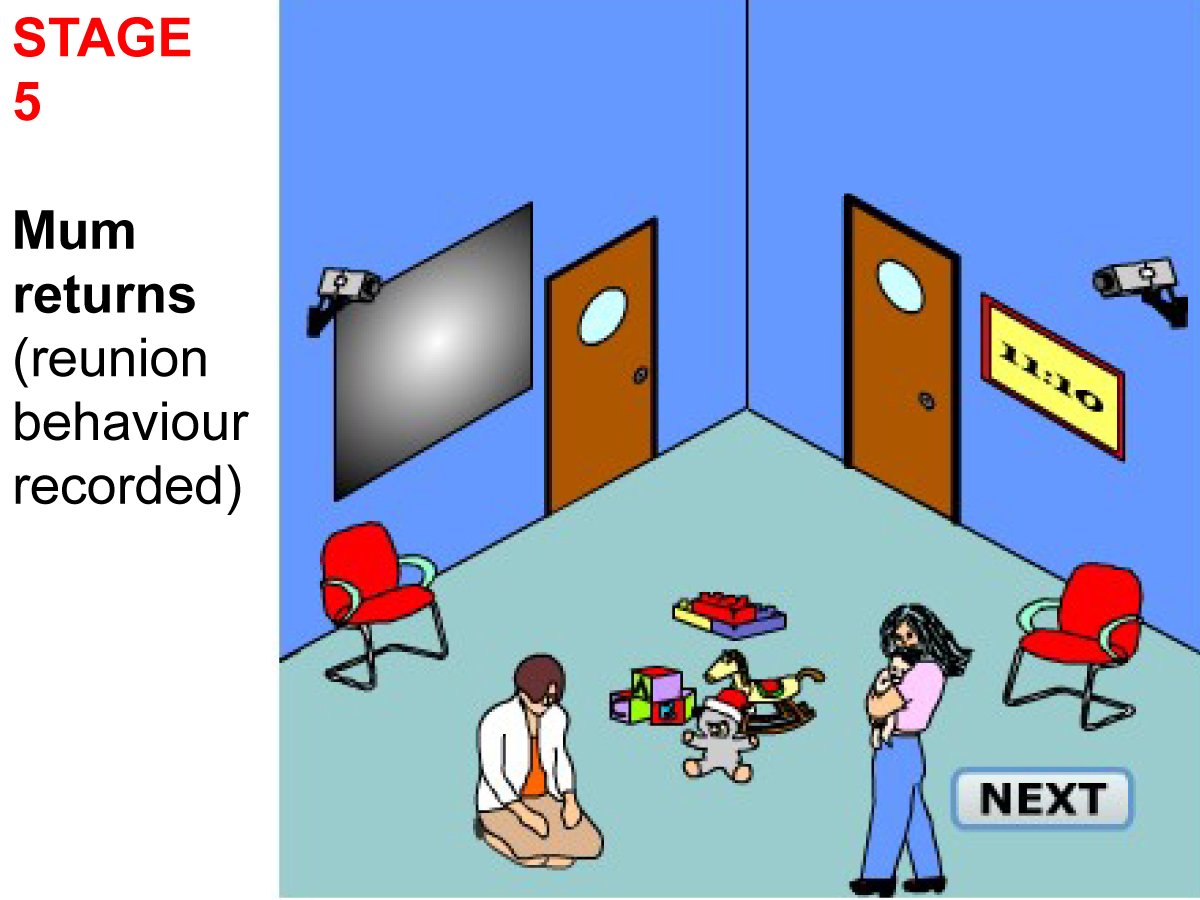

Episode 5: Mother Returns, Stranger Leaves

-

Who is present: Mother and baby (initially stranger, who then leaves).

-

Duration: Variable, typically short.

-

Purpose: Observe the infant’s reunion behavior upon the mother’s return, crucial for assessing attachment style.

-

Description: Researchers carefully note the baby’s immediate reaction—approach, avoidance, resistance, or ambivalence.

The mother pauses briefly at the doorway for spontaneous infant reaction while the stranger discreetly leaves. Once the baby resumes playing, the mother prepares to leave again, saying bye-bye.

-

Behaviors observed: Observers closely recorded the baby’s reunion behaviors, noting efforts to regain closeness, maintain physical contact, or behaviors indicating avoidance or resistance.

-

Categories: Proximity and contact seeking, Contact maintaining, Avoidance of proximity and contact, Resistance to contact and comfort.

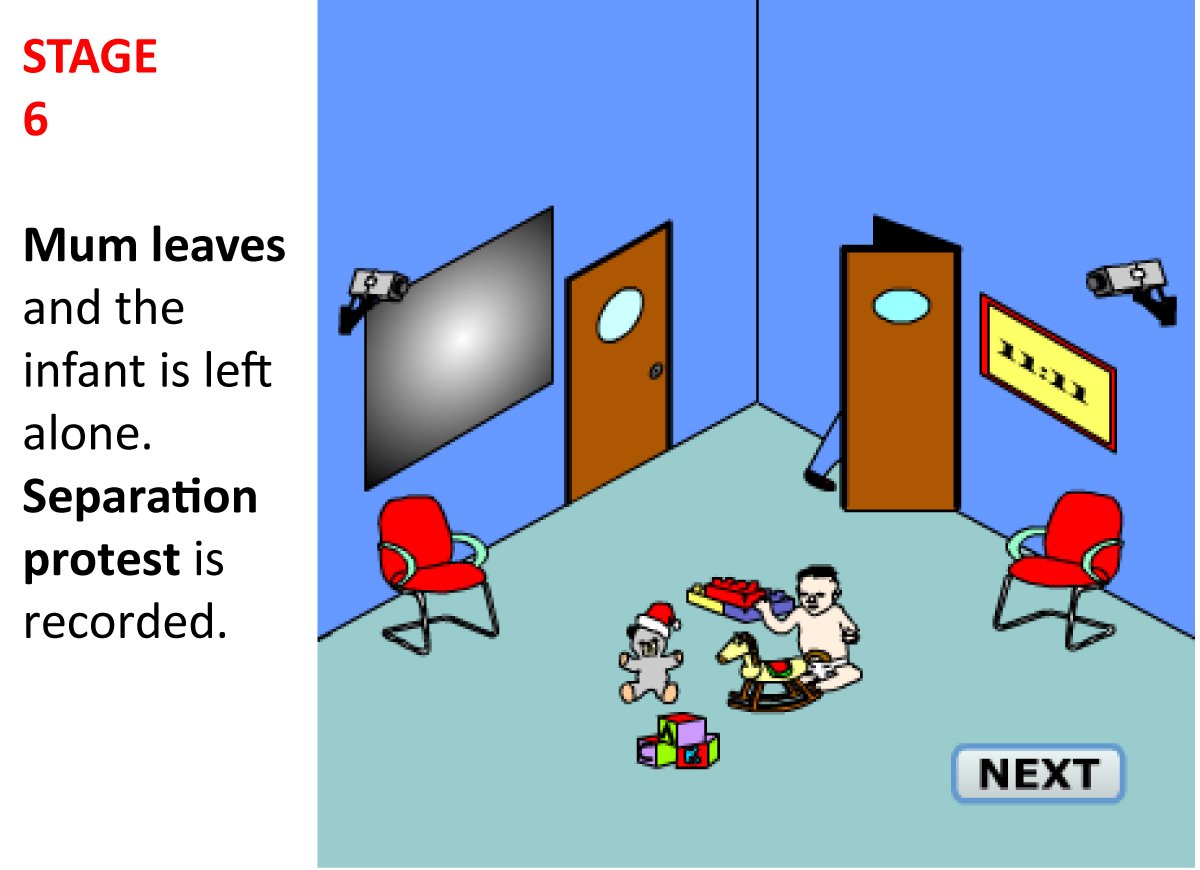

Episode 6: Mother Leaves, Infant Completely Alone

-

Who is present: Baby only.

-

Duration: Up to three minutes, shorter if distress is significant.

-

Purpose: Clearly evaluate the infant’s reaction to complete isolation, emphasizing the intensity of separation anxiety.

-

Description: Observers specifically note signs of significant anxiety like crying, attempts to follow, or movements toward the door.

-

Behaviors observed: Observers specifically noted how actively and persistently the baby searched for the absent mother and indicated distress through specific search behaviors.

-

Categories: Search behavior.

Episode 7: Stranger Returns

-

Who is present: Baby and stranger.

-

Duration: Up to three minutes, shorter if distress is significant.

-

Purpose: Assess the infant’s willingness to accept comfort from the stranger after experiencing total isolation.

- Description: The Stranger enters the room and behaves as they did in Episode 4. In Episode 4, the Stranger’s behavior was contingent on the baby’s state:

If the baby was happily playing, the Stranger was non-participant; if the baby was inactive, the Stranger tried to interest them in toys; and if the baby was distressed, the Stranger attempted to distract or comfort them

-

Behaviors observed: Observers evaluated if and how the baby accepted comfort or interaction from the stranger, noting any search behaviors directed toward the mother’s last known location.

-

Categories: Search behavior, Avoidance of proximity and contact, Resistance to contact and comfort.

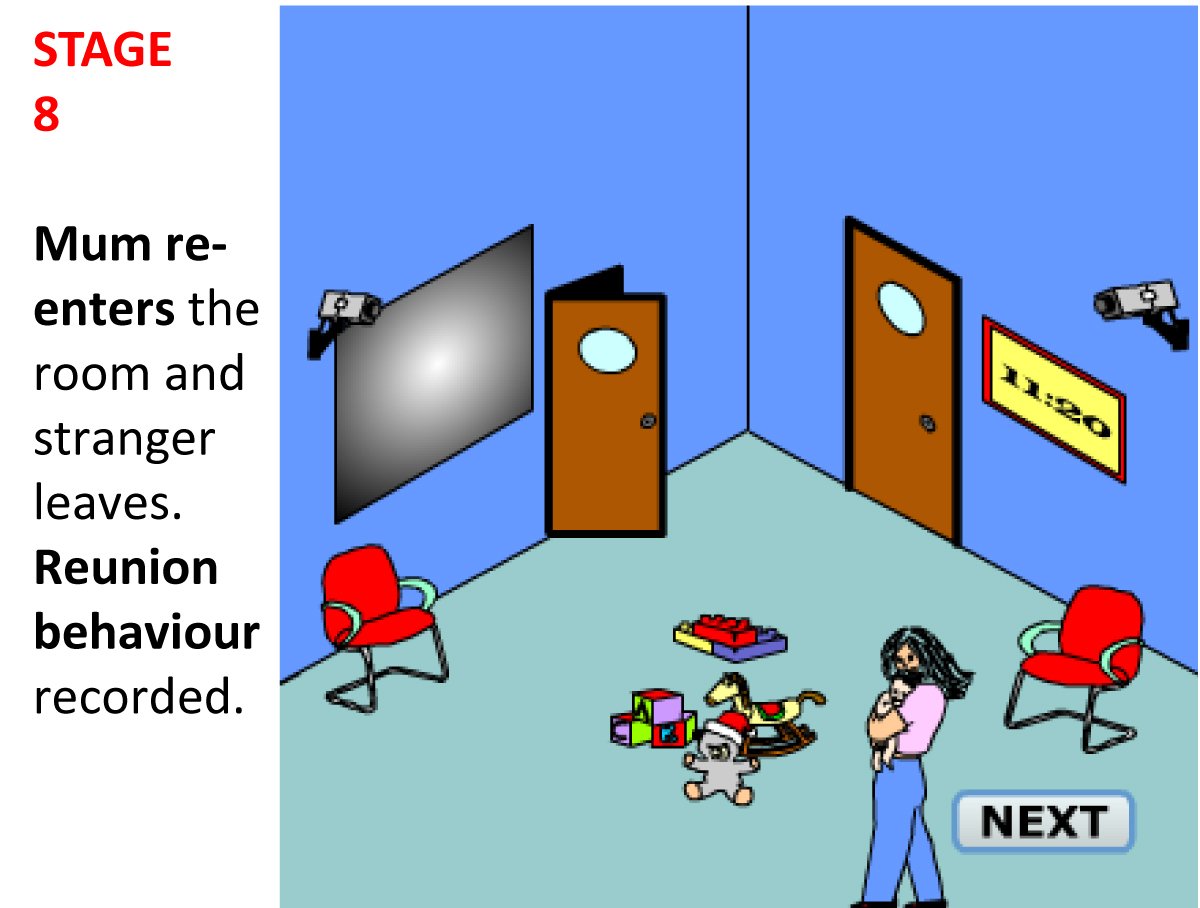

Episode 8: Mother Returns, Stranger Leaves (Final Reunion)

-

Who is present: Mother and baby (initially stranger, who then leaves).

-

Duration: Variable, typically short.

-

Purpose: Conduct a final observation of infant’s reunion behavior to determine how quickly and effectively they are comforted by their caregiver after multiple separations.

-

Description: The mother returns, the stranger exits, and the mother-baby reunion interaction is carefully observed and recorded, concluding the procedure.

-

Behaviors observed: Observers carefully assessed the baby’s final reunion behaviors, observing how quickly the baby sought and maintained contact with the mother or demonstrated avoidance or resistance.

-

Categories: Proximity and contact seeking, Contact maintaining, Avoidance of proximity and contact, Resistance to contact and comfort.

Observational Scoring

In the Strange Situation procedure, trained observers closely monitored specific infant behaviors to understand their attachment patterns.

Observers recorded how infants explored, responded when separated from their caregivers, reacted to strangers, and behaved during reunions.

Observational Procedure

-

Observations were conducted discretely through a one-way mirror, ensuring infants and mothers behaved naturally.

-

Typically, two observers narrated continuous, detailed accounts into a two-channel tape recorder, marking behaviors every 15 seconds, synchronized with a timer’s click.

-

During early observations (first 14 infants), one observer spoke into the recorder while the other wrote notes by hand. Later, for the next 33 infants, only one observer (Bell) narrated continuously.

-

Afterwards, these recordings were carefully transcribed, combined, and coded for detailed analysis.

Behaviors Observed

The behaviors observed outline the general types of actions that observers specifically looked for during the Strange Situation test. These behaviors serve as a foundation or raw data.

The observers noted the behavior displayed during 15-second intervals and scored the behavior for intensity on a scale of 1 to 7.

-

Exploratory Behavior: How babies explored their surroundings—such as playing with toys, moving around, or looking around curiously.

-

Separation Anxiety: How babies showed distress when their caregiver left, including crying, protesting, or searching for their caregiver.

-

Stranger Anxiety: How babies reacted emotionally to a stranger’s presence, showing either distress, curiosity, or comfort.

-

Reunion Behavior: How babies responded when reunited with their caregiver, critical for understanding attachment styles.

-

Search Behaviors: Actions babies took to find their absent caregiver, like following the caregiver to the door, trying to open it, or staring at the caregiver’s empty chair.

-

Negative Affect Displays: Clear signs of discomfort or distress, such as crying, sadness, or frustration.

Categories for Behavior Scoring

Behavioral categories allow the researcher to tally observations into pre-arranged groupings. It also makes the observations replicable, so the results have greater reliability.

Essentially, the general behaviors observed are categorized based on their purpose and meaning in the context of attachment.

These four classes of behavior were scored for interaction with the mother in episodes 2, 3, 5, and 8, and for interaction with the stranger in episodes 3, 4, and 7.

1. Proximity and contact seeking:

Behaviors involve active efforts such as purposeful approaching, climbing, gesturing (like reaching or leaning), partial approaches, and directed cries.

The criteria include the child’s initiative, persistence, and effectiveness in gaining (or regaining) contact or proximity.

The score reflects the intensity and nature of the child’s efforts across different episodes.

2. Contact maintaining:

Behaviors relevant after the baby has made physical contact, either self-initiated or otherwise.

They encompass clinging, embracing, resisting release through intensified clinging or turning back and reaching if contact is lost, and vocal protestations.

3. Avoidance of proximity and contact:

Interaction-avoiding behaviors apply in situations that typically incite approach or interaction, such as an adult entering or trying to attract the baby’s attention.

The behaviors indicative of avoidance include increasing distance, turning away, averting gaze, hiding the face, or ignoring the person, especially when the person is attempting to engage the child’s attention.

Unlike the resistance variable, which is often associated with anger, avoidance may have a neutral tone or reflect apprehension.

It may be seen as a defensive behavior that conceals feelings, possibly including resentment.

The coding for this variable distinguishes between the child’s interactions with the mother and a stranger.

4. Resistance to contact and comfort:

Assesses the child’s resistant behavior towards someone who attempts to interact or come into proximity.

Contact- and interaction-resisting behaviors include angry, conflicting attempts to repel the adult, wriggling to get down if picked up, or rejecting toys used by the adult to interact.

Other indications could be angry screams, thrashing about, pouting, irritable fussing, or showing petulance.

These resistant behaviors may alternate with efforts to maintain contact with the person being rejected.

5. Search behavior:

During episodes 4, 6, and 7, search behaviors were recorded.

These included following the mother to the door, attempting to open it, banging on it, keeping the focus on the door or glancing towards it, approaching the mother’s empty chair, or observing it.

These behaviors indicated the infant’s active search or orientation towards the last seen location of the absent mother (usually the door) or a place associated with her in the unfamiliar setting (her chair).

How Behaviors Were Scored

Observers rated each behavior every 15 seconds, using a clear intensity scale from 1 (very weak or minimal) to 7 (strong or highly intense). Scores considered:

-

Strength: How strongly or vigorously the baby showed a behavior.

-

Frequency: How often the behavior occurred.

-

Duration: How long the behavior lasted.

-

Latency: How quickly or slowly the behavior began after a specific event.

-

Type: Active behaviors (like reaching or crawling) scored higher than passive signals (like quiet vocalizations or facial expressions).

Reliability of Observations

To ensure the scoring was accurate and reliable, separate observers independently reviewed recorded behaviors. Observations showed excellent reliability:

-

A near-perfect correlation of 0.99 for movements, exploration, and play behaviors.

-

A correlation of 0.98 for crying and other distress behaviors, demonstrating consistent and reliable scoring.

Results [Attachment Styles]

Ainsworth (1970) identified three main attachment styles, secure (type B), insecure avoidant (type A), and insecure ambivalent/resistant (type C).

She concluded that these attachment styles resulted from early interactions with the mother.

A fourth attachment style, known as disorganized, was later identified (Main, & Solomon, 1990).

| Secure | Resistant | Avoidant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Anxiety | Distressed when mother leaves | Intense distress when the mother leaves | No sign of distress when the the mother leaves |

| Stranger Anxiety | Avoidant of stranger when alone, but friendly when the mother is present | The infant avoids the stranger – shows fear of the stranger | The infant is okay with the stranger and plays normally when the stranger is present |

| Reunion behavior | Positive and happy when mother returns | The infant approaches the mother, but resists contact, may even push her away | The Infant shows little interest when the mother returns |

| Other | Uses the mother as a safe base to explore their environment | The infant cries more and explores less than the other two types | The mother and stranger are able to comfort the infant equally well |

| % of infants | 70% | 15% | 15% |

B: Secure Attachment

Secure attachment was the most commonly observed attachment type in Mary Ainsworth’s original Strange Situation studies.

It describes children who have developed a strong sense of trust and comfort with their caregivers, typically due to caregivers consistently responding sensitively to their needs.

According to attachment theorist John Bowlby (1980), securely attached individuals hold an internal belief or expectation (representational model) that their attachment figures are “available, responsive, and helpful” (p. 242).

Similarly, Main and Cassidy (1988) noted that securely attached children confidently rely on their caregiver as a “safe base” from which to explore and return to for comfort during stressful situations.

General Characteristics of Securely Attached Infants:

-

They confidently explore their environment when the caregiver is present.

-

They experience moderate distress when separated from their caregiver.

-

They typically show moderate stranger anxiety.

-

They seek comfort and are easily soothed by their caregiver upon reunion.

Example of Secure Attachment:

Imagine a toddler entering a room filled with toys. The child confidently explores the toys but occasionally returns to the mother, perhaps showing her a toy or briefly seeking reassurance.

When the mother leaves, the child visibly becomes upset, cries, and seems anxious.

However, once the mother returns, the child quickly approaches her, is comforted easily, and soon resumes playing happily.

Detailed Behaviors in the Strange Situation Procedure:

In the context of the Strange Situation, a child displaying secure attachment exhibits the following behaviors:

-

Desire for Proximity and Contact: The baby actively seeks proximity and contact with the mother, especially during reunion episodes. This desire reflects a strong emotional connection and trust in the mother as a source of comfort and safety.

-

Maintenance of Contact: Once in contact with the mother, the baby seeks to maintain it. If the mother attempts to put the baby down, the child may resist or protest, indicating a preference to stay close.

-

Positive Response to Reunion: The baby’s response to the mother’s return is more than casual. It may include a smile, cry, or tendency to approach, signaling happiness or relief at the mother’s presence.

-

Lack of Resistance or Avoidance: The baby shows little or no tendency to resist or avoid contact or interaction with the mother during reunion episodes. This lack of avoidance or resistance is indicative of a secure and comfortable relationship.

-

Preference for Mother Over Stranger: While the baby may or may not be friendly with a stranger, there is a clear preference for interaction and/or contact with the mother. This preference underscores the special bond between the child and the mother.

-

Distress Related to Mother’s Absence: If the baby is distressed during separation episodes, it is clearly related to the mother’s absence rather than merely being alone. The baby may find some comfort in the stranger, but it is evident that the mother is the preferred source of comfort.

-

No Avoidance of Mother: The baby shows little or no tendency to avoid the mother in the reunion episodes, reflecting a lack of apprehension or fear in the relationship.

A: Insecure Avoidant

Avoidant attachment is a pattern observed in some infants, characterized by emotional distance, independence, and minimal visible reliance on caregivers.

Infants classified as having avoidant attachment typically showed little reaction to their caregiver’s departures or returns and displayed minimal difference in behavior toward strangers and caregivers.

General Characteristics of Avoidant Attachment:

-

Avoidant infants often appear independent both physically and emotionally. They usually explore their environment without seeking reassurance or comfort from their caregiver.

-

They exhibit minimal or no distress when separated from their caregiver. Any distress shown generally results from being left alone, rather than specifically due to the caregiver’s absence.

-

During reunions, avoidant children show limited interest or excitement and often ignore or avoid interaction with their caregiver.

-

Avoidant infants tend to treat strangers similarly to their caregivers, displaying little emotional differentiation.

Reasons Behind Avoidant Attachment (Caregiver Behavior):

Infants generally develop an avoidant attachment when caregivers are consistently insensitive or unresponsive to their emotional needs.

Caregivers of avoidantly attached infants frequently withdraw support during challenging situations and may be emotionally unavailable or indifferent when the infant is distressed (Ainsworth, 1979; Stevenson-Hinde & Verschueren, 2002).

Detailed Behaviors in the Strange Situation Procedure:

In the context of the Strange Situation, a child displaying avoidant attachment exhibits the following behaviors:

-

Avoidance of Proximity and Interaction: In the reunion episodes, the baby conspicuously avoids proximity to or interaction with the mother. This avoidance may manifest as ignoring the mother upon her return, greeting her casually, or mingling a welcome with avoidance responses such as turning away, moving past, or averting the gaze.

-

Lack of Desire for Proximity or Contact: The baby shows little or no tendency to seek proximity, interaction, or contact with the mother, even during reunion episodes. This lack of desire reflects an emotional distance and a lack of reliance on the mother for comfort or security.

-

No Clinging or Resistance to Release: If the baby is picked up, there is little or no tendency to cling or resist being released. This behavior further emphasizes the lack of attachment or need for closeness with the mother.

-

Minimal Active Resistance to Contact: There is little or no tendency toward active resistance to contact or interaction with the mother. If the baby is picked up, there may be squirming to get down, but not a strong rejection or anger.

-

Similar Treatment of Stranger: The baby treats the stranger much like the mother, although perhaps with less avoidance. This lack of differentiation between the mother and a stranger indicates a lack of special attachment or preference for the mother.

-

Lack of Distress During Separation: The baby is not distressed during separation, or the distress seems to be due to being left alone rather than the mother’s absence. This lack of distress related to the mother’s absence further highlights the lack of attachment or reliance on the mother for emotional support.

-

Possible Indifference to Being Alone: The text cuts off, but it seems to imply that distress does not occur when left alone for most babies with avoidant attachment. This indifference to being alone or with the mother reflects a lack of emotional connection or dependence on the mother.

C: Insecure Ambivalent / Resistant

Ambivalent (also called resistant) attachment describes children who experience mixed feelings of dependency and anger toward their caregiver due to inconsistent emotional caregiving.

General Behavioral Characteristics:

Children with ambivalent attachment typically exhibit behaviors characterized by anxiety, dependency, and conflicting emotions toward their caregivers. Specifically, these children:

-

Appear clingy and anxious in new or unfamiliar environments, showing reluctance or inability to explore freely.

-

Become intensely distressed and visibly upset when separated from their caregivers (strong separation anxiety).

-

Display fear or anxiety when encountering unfamiliar people (stranger anxiety).

-

Exhibit mixed emotional responses during reunions—initially seeking comfort but then resisting or rejecting efforts by caregivers to comfort them.

-

Are generally difficult to soothe when upset, reflecting their underlying insecurity and anxiety about caregiver responsiveness.

Example of Ambivalent Attachment Behavior:

Imagine a child entering a new playroom with their mother. Rather than confidently exploring, this child remains close, clinging tightly and hesitating to interact with toys.

When the mother leaves briefly, the child panics and becomes extremely distressed, crying loudly and showing clear anxiety.

Upon the mother’s return, the child initially seeks comfort but quickly becomes frustrated or even angry, pushing her away, resisting physical comfort, or continuing to fuss despite attempts to soothe them.

Why Ambivalent Attachment Develops:

Ambivalent attachment typically emerges due to caregivers who are inconsistent in responding to their child’s emotional needs.

Sometimes these caregivers may be responsive and comforting, while at other times, they might ignore or misinterpret their child’s signals.

Because the child never knows what response to expect, they become anxious and insecure, leading to the conflicting behaviors observed in the Strange Situation.

Detailed Behaviors in the Strange Situation Procedure:

In the context of the Strange Situation, a child displaying anxious resistant attachment exhibits the following behaviors:

-

Conspicuous Contact- and Interaction-Resisting Behavior: The baby displays noticeable resistance to contact and interaction, especially in specific episodes like Episode 8.

This resistance may manifest as pushing away, squirming, or showing anger when approached or picked up by the mother.

-

Ambivalence Towards the Mother: Despite the resistance, the baby also shows moderate-to-strong seeking of proximity and contact and strives to maintain contact once gained.

This combination of seeking closeness and resisting contact gives the impression of being ambivalent toward the mother, reflecting mixed feelings and confusion.

-

No Avoidance of the Mother: Unlike avoidant attachment, the baby with resistant attachment shows little or no tendency to ignore the mother in the reunion episodes or to turn or move away from her or avert his gaze. This lack of avoidance indicates a desire for connection, even if it is conflicted.

-

Possibly More Angry or Passive: The baby may display generally “maladaptive” behavior in the strange situation. This could manifest as a tendency to be more angry than infants in other groups, reflecting frustration or confusion.

Alternatively, the baby may be conspicuously passive, possibly reflecting a lack of confidence or uncertainty in how to respond.

-

Complex Relationship with the Caregiver: The combination of seeking proximity and resisting contact reflects a complex and often stressful relationship with the caregiver. The baby may want closeness but also feel frustration or anger, leading to a pattern of behavior that is both seeking and rejecting.

Conclusion

A child’s sense of emotional security and trust in relationships develops significantly during their first year of life, primarily shaped by the caregiver’s responsiveness.

According to Ainsworth’s (1978) caregiver sensitivity hypothesis:

Mothers who consistently and promptly respond to their infant’s emotional signals – such as cries, gestures, or facial expressions -typically foster secure attachments.

These securely attached infants trust that their caregiver will be accessible, responsive even when physically apart, and reliable in comforting them when distressed (Stayton & Ainsworth, 1973).

Conversely, inconsistent or insensitive caregiving often results in insecure attachments.

When caregivers respond unpredictably – sometimes comforting the child’s distress and sometimes ignoring it -infants tend to develop an insecure ambivalent attachment.

Such children display heightened anxiety, emotional volatility, and mixed feelings of dependence and resistance toward caregivers.

When caregivers frequently neglect, ignore, or reject their child’s emotional needs, infants typically develop an insecure avoidant attachment, becoming emotionally distant and overly self-reliant due to their learned belief that signaling their needs has little impact on their caregiver.

Internal Working Models

These early attachment experiences profoundly influence a child’s internal working models – the mental frameworks that guide their expectations and interactions in later relationships (Bowlby, 1969).

- Securely attached children generally perceive themselves positively, as deserving of care and respect, and view others as supportive and reliable (Jacobsen & Hoffman, 1997).

- Avoidantly attached children tend to internalize rejection, developing negative self-images and assuming they are unworthy of affection or attention (Larose & Bernier, 2001).

- Ambivalently attached children frequently exaggerate their emotional responses and have inconsistent self-perceptions due to the unpredictability of their caregivers’ support (Kobak et al., 1993).

Ultimately, Ainsworth’s findings provided essential empirical support for Bowlby’s attachment theory, highlighting the critical importance of sensitive and responsive caregiving.

This research underscores how early interactions profoundly shape emotional health, relationship expectations, and social development throughout life.

Theoretical Evaluation

1. culture bias

The Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) has faced criticism for being culturally biased, often described as a culture-bound test.

It was initially created by American psychologist Mary Ainsworth, drawing from British psychiatrist John Bowlby’s attachment theory, reflecting predominantly Western norms and caregiving styles.

Using such culturally specific approaches universally is known as an imposed etic, which can lead to misunderstandings and inaccurate assessments across diverse cultural groups.

The cultural meanings attached to separation and reunion vary significantly worldwide, calling into question the ecological validity (real-world accuracy) of the SSP.

Why is the Strange Situation Culturally Biased?

-

Different Childhood Experiences: Childhood experiences vary widely across cultures, shaping how children react in situations like the SSP. What seems typical or “normal” in one culture might be unusual or stressful in another.

-

Varied Caregiving Practices: Caregiving styles differ greatly around the world, directly influencing children’s reactions during separations and reunions. Practices considered appropriate and nurturing in one culture might appear insensitive or neglectful in another.

-

Diverse Cultural Views on Emotional Expression: Cultures differ significantly in how they view emotional expression. Some encourage emotional openness and expressiveness, while others value emotional control and restraint, impacting how children show their feelings during tests like the SSP.

Real-World Cross-Cultural Examples:

-

Japan: Researcher Takahashi discovered the SSP didn’t effectively measure attachment in Japan due to traditional caregiving practices emphasizing constant closeness – such as co-sleeping, co-bathing, and always carrying the infant.

Short separations during the SSP caused significant distress, sometimes resulting in securely attached Japanese infants being misclassified as ambivalent or resistant because of their intense reactions.

This misclassification showed the SSP’s limited applicability to traditional Japanese caregiving contexts.

-

Germany: Grossmann and colleagues found that in northern Germany, mothers often encouraged independence early in life. Many infants displayed behaviors classified by the SSP as “avoidant” attachment, such as minimal distress when separated and low-key reunions.

However, these behaviors reflect culturally valued independence rather than insecure attachment. The SSP, therefore, misinterpreted culturally appropriate behaviors as problematic, exemplifying cultural bias.

-

Uganda (Ganda Infants): Observations revealed culturally specific greeting behaviors among Ganda infants, such as hand-clapping, which differed from typical Western greetings like hugging and kissing.

These differences illustrate how culturally influenced behaviors might be misunderstood or misclassified within the SSP, highlighting its limited cultural sensitivity.

2. caregiver sensitivity theory

This caregiver sensitivity theory is supported by research from Wolff and Van Ijzendoorn (1997), who conducted a meta-analysis (a review) of research into attachment types.

They found that there is a relatively weak correlation of 0.24 between parental sensitivity and attachment type – generally more sensitive parents had securely attached children.

However, in evaluation, critics of this theory argue that the correlation between parental sensitivity and the child’s attachment type is only weak.

This suggests that there are other reasons which may better explain why children develop different attachment types and that the maternal sensitivity theory places too much emphasis on the mother.

Focusing just on maternal sensitivity when explaining why children have different attachment types is, therefore, a reductionist approach.

3. temperament

An alternative theory proposed by Kagan (1984) suggests that the temperament of the child is actually what leads to the different attachment types.

Children with different innate (inborn) temperaments will have different attachment types.

This theory is supported by research from Fox (1989), who found that babies with an ‘Easy’ temperament (those who eat and sleep regularly and accept new experiences) are likely to develop secure attachments.

Babies with a ‘slow to warm up’ temperament (those who took a while to get used to new experiences) are likely to have insecure-avoidant attachments.

Babies with a ‘Difficult’ temperament (those who eat and sleep irregularly and who reject new experiences) are likely to have insecure-ambivalent attachments.

In conclusion, the most complete explanation of why children develop different attachment types would be an interactionist theory.

This would argue that a child’s attachment type is a result of a combination of factors – both the child’s innate temperament and their parent’s sensitivity towards their needs.

4. interactionist theory

Belsky and Rovine (1987) propose an interactionist theory to explain the different attachment types.

They argue that the child’s attachment type is a result of both the child’s innate temperament and also how the parent responds to them (i.e., the parents’ sensitivity level).

Additionally, the child’s innate temperament may, in fact, influence the way their parent responds to them (i.e, the infants’ temperament influences the parental sensitivity shown to them).

To develop a secure attachment, a ‘difficult’ child would need a caregiver who is sensitive and patient for a secure attachment to develop.

5. Meta-analysis

Madigan et al. (2023) conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis on 285 studies involving over 20,000 infant-caregiver pairs to estimate the global distribution of attachment classifications derived from the SSP: secure (51.6%), avoidant (14.7%), resistant (10.2%), and disorganized (23.5%).

The meta-analysis found no differences in attachment distribution by child age or sex.

There was also no difference between mothers and fathers in rates of secure, avoidant, resistant, or disorganized attachment. However, attachment distributions did differ across other moderators.

Higher rates of avoidant and disorganized attachment were found in families with socioeconomic risks.

Children who experienced maltreatment had extremely high rates of disorganized attachment (64%) compared to non-maltreated children (22%).

Infants placed in foster or adoptive care showed less avoidant attachment but higher disorganized attachment versus biologically related dyads.

A notable finding was a temporal trend showing decreased avoidant attachment over time, perhaps reflecting changes in parenting styles or measurement.

Regional differences were also found – Asia, Africa, and South America showed deviations from the North American distribution.

The meta-analysis provides a definitive estimate of the prevalence of secure infant-parent attachment globally (51.6%), supporting the notion that secure attachment is likely to occur when stressors and risks imposed on the parent-infant relationship are minimal.

However, more research is needed on cultural differences in attachment and validity of the SSP across diverse groups.

The study also highlights factors like socioeconomic disadvantage and trauma that disrupt secure attachment formation.

Methodological Evaluation

1. reliability

The strange situation classification has been found to have good reliability. This means that it achieves consistent results.

For example, a study conducted in Germany found that 78% of the children were classified in the same way at ages 1 and 6 years (Wartner et al., 1994).

2. validity

Although, as Melhuish (1993) suggests, the Strange Situation is the most widely used method for assessing infant attachment to a caregiver, Lamb et al. (1985) have criticized it for being highly artificial and lacking ecological validity.

The child is placed in a strange and artificial environment, and the procedure of the mother and stranger entering and leaving the room follows a predetermined script of eight stages (e.g., mum and stranger entering and leaving the room at set times) that would be unlikely to happen in real life.

I have been quite disappointed that so many attachment researchers have gone on to do research with the Strange Situation rather than looking at what happens at the home or in other natural settings—like I said before, it marks a turning away from “field work,” and I don’t think it’s wise. (Ainsworth & Marvin, 1995, p. 12).

The artificial environment of the SSP may not activate the attachment system for all infants, meaning some children could be misclassified (Ziv & Hotam, 2015).

For example, avoidant infants may not actually feel stressed when separated from caregivers in this unfamiliar setting. Limited evidence exists linking avoidant behavior in the SSP to physical markers of stress.

Additionally, SSP classifications show only modest connections to expected correlates like maternal sensitivity.

A problem of the study is that it lacks population validity. The original study used American infants from middle-class families.

The study tells us about how this particular group behaves and cannot be generalized to the broader population and other cultures, which might behave differently towards their children and have different expectations.

For example, in Germany, parents encourage independence in their children, so they are less likely to show enthusiastic reunion behavior than children from other cultures.

Mary Ainsworth concluded that the strange situation could be used to identify the child’s type of attachment but has been criticized because it identifies only the type of attachment to the mother.

The child may have a different type of attachment to the father or grandmother, for example (Lamb, 1977). This means that it lacks validity, as it does not measure a general attachment style, but instead an attachment style specific to the mother.

In addition, some research has shown that the same child may show different attachment behaviors on different occasions.

Children’s attachments may change, perhaps because of changes in the child’s circumstances, so a securely attached child may appear insecurely attached if the mother becomes ill or the family circumstances change.

3. ethics

The strange situation has also been criticized on ethical grounds.

Because the child is put under stress (separation and stranger anxiety), the study has broken the ethical guidelines for the protection of participants.

However, in its defense, the separation episodes were curtailed prematurely if the child became too stressed.

Also, according to Marrone (1998), although the Strange Situation has been criticized for being stressful, it simulates everyday experiences, as mothers leave their babies for brief periods in different settings and often with unfamiliar people such as babysitters.

4. categorial measurement

The categorical approach to classification may be too reductive to fully capture the complexity of infant attachment patterns (Ziv & Hotam, 2015).

Reducing attachment security to four rigid categories treats the SSP as a “weigh scale” reflecting a “true score” when attachment is likely more continuous and multidimensional.

This oversimplification could hamper the refinement of attachment theory if inconsistencies are attributed to limitations of the theory rather than the measure.

Infant attachment is complex, with individual differences likely being continuous rather than falling neatly into discrete categories.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Mary Ainsworth’s contributions to psychology

Mary Ainsworth significantly contributed to psychology by developing the ‘Strange Situation’ procedure to observe attachment relationships between a caregiver and child.

Her work shaped our understanding of attachment styles: secure, avoidant, and ambivalent, greatly influencing developmental and child psychology.

How is the Strange Situation important?

The Strange Situation experiment is important because it was a breakthrough in identifying different attachment styles in infants.

Ainsworth’s research showed that how caregivers respond to a child’s needs can have a lasting impact on their emotional development. The experiment provided a reliable way to measure attachment styles, which has helped researchers and clinicians better understand how attachment influences a person’s relationships throughout their life.

Ainsworth’s work has also influenced how parents and caregivers understand the importance of emotional responsiveness and sensitive care in promoting secure attachment and healthy child development.

Can a child’s attachment style change over time?

Yes, a child’s attachment style can change over time. While attachment styles tend to be stable, experiences with caregivers and changes in the child’s environment can lead to shifts in attachment style.

For example, a child with an insecure attachment style may become more secure with consistent and responsive caregiving. Conversely, a child with a secure attachment style may develop an insecure attachment style due to neglect, abuse, or other adverse experiences.

Is Ainsworth research ethnocentric?

Ethnocentrism is when someone thinks their own cultural or ethnic group is the most important, and they judge other cultures or ethnic groups based on their own standards and values. They may see other groups as inferior or less important.

Some researchers argue that Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation experiment is ethnocentric because it was originally conducted on a relatively small sample of middle-class American families.

Critics argue that the experiment may not represent attachment patterns in other cultures and may not account for cultural differences in child-rearing practices.

What is the difference between secure and insecure attachment?

Secure and insecure attachments are broad classifications that describe how we think, feel, and behave in relationships.

Secure attachment in adults is characterized by trust, stability, and a balance between intimacy and independence. Insecure attachment (anxious, avoidant, or disorganized) can involve fear of abandonment, emotional distance, or inconsistent reactions to intimacy and conflict.

What is the difference between Bowlby and Ainsworth’s attachment theory.

Bowlby created the overall framework of attachment theory, emphasizing the evolutionary purpose and psychological mechanisms of attachment.

Mary Ainsworth took Bowlby’s broad theoretical ideas and made them testable through observation and experiments.

Her key contribution was developing the Strange Situation Procedure, an experiment that clearly and consistently measured how infants behave when separated from their caregivers and then reunited.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. (1964). Patterns of attachment behavior shown by the infant in interaction with his mother. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of behavior and Development, 51-58.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of love.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1979). Attachment as related to mother-infant interaction. In Advances in the study of behavior (Vol. 9, pp. 1-51). Academic Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41, 49-67.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1971) Individual differences in strange- situation behavior of one-year-olds. In H. R. Schaffer (Ed.) The origins of human social relations. London and New York: Academic Press. Pp. 17-58.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ainsworth, M., & Marvin, R. (1995). On the shaping of attachment theory and research: An interview with Mary D. S. Ainsworth. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 60(Serial No. 244), 3–24.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Wittig, B. A. (1969). Attachment and exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In B. M. Foss(Ed. ), Determinants of infant behavior (Vol. 4,pp. 111-136). London: Methuen.

Behrens, K. Y., Hesse, E., & Main, M. (2007). Mothers” attachment status as determined by the Adult Attachment Interview predicts their 6-year-olds” reunion responses: A study conducted in Japan. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1553.

Belsky, J., & Rovine, M. (1987). Temperament and attachment security in the strange situation: An empirical rapprochement. Child development, 787-795.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss . New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness & depression. Attachment and loss (vol. 3); (International psycho-analytical library no.109). London: Hogarth Press.

Fox, N. A. (1989). Infant temperament and security of attachment: a new look. International Society for behavioral Development, J yviiskylii, Finland.

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Spangler, G., Suess, G., & Unzner, L. (1985). Maternal sensitivity and newborns’ orientation responses as related to quality of attachment in northern Germany. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 233-256.

Jacobsen, T., & Hoffman, V. (1997). Children’s attachment representations: Longitudinal relations to school behavior and academic competency in middle childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 33, 703-710.

Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., Clarke, C., Snidman, N., & Garcia-Coll, C. (1984). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child development, 2212-2225.

Kobak, R. R., Cole, H. E., Ferenz-Gillies, R., Flemming, W. S., & Gamble, W. (1993). Attachment and emotional regulation during mother-teen problem-solving. A control theory analysis. Child Development, 64, 231-245.

Lamb, M. E. (1977). The development of mother-infant and father-infant attachments in the second year of life. Developmental Psychology, 13, 637-48.

Larose, S., & Bernier, A. (2001). Social support processes: Mediators of attachment state of mind and adjustment in later late adolescence. Attachment and Human Development, 3, 96-120.

Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M. P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Duschinsky, R., Schuengel, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Ly, A., Cooke, J. E., Deneault, A.-A., Oosterman, M., & Verhage, M. L. (2023). The first 20,000 strange situation procedures: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 149(1-2), 99–132.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M.T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti & E.M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the Preschool Years (pp. 121–160). Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Marrone, M. (1998). Attachment and interaction . Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Melhuish, E. C. (1993). A measure of love? An overview of the assessment of attachment. ACPP Review & Newsletter, 15, 269-275.

Stayton, D. J., & Ainsworth, M. D. (1973). Individual differences in infant responses to brief, everyday separations as related to other infant and maternal behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 9(2), 226.

Schaffer, H. R., & Emerson, P. E. (1964) The development of social attachments in infancy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 29(3), serial number 94.

Schmidt, W. J., Keller, H., & Rosabal Coto, M. (2021). Development in context: What we need to know to assess children’s attachment relationships. Developmental Psychology, 57(12), 2206 2219.

Stevenson-Hinde, J., & Verschueren, K. (2002). Attachment in childhood. status: published.

Takahashi, K. (1986). Examining the strange-situation procedure with Japanese mothers and 12-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 22(2), 265.

Takahashi, K. (1990). Are the key assumptions of the ‘Strange Situation’procedure universal? A view from Japanese research. Human development, 33(1), 23-30.

Thompson, R. A., Gardner, W., & Charnov, E. L. (1985). Infant-mother attachment: The origins and developmental significance of individual differences in Strange Situation behavior. LEA.

Wartner, U. G., Grossman, K., Fremmer-Bombik, I., & Guess, G. L. (1994). Attachment patterns in south Germany. Child Development, 65, 1014-27.

Wolff, M. S., & Ijzendoorn, M. H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta‐analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment . Child development, 68(4), 571-591.

Ziv, Y., & Hotam, Y. (2015). Theory and measure in the psychological field: The case of attachment theory and the strange situation procedure. Theory & Psychology, 25(3), 274-291.

Further Reading

- BPS Article- Overrated: The predictive power of attachment

- The Ainsworth Strange Situation (Lecture Slides)

- Scoring for the Strange Situation

- A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship

- Cross-cultural Patterns of Attachment: A Meta-Analysis of the Strange Situation

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.