Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is defined by “a pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy” that impairs functioning across multiple areas of life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

People with NPD may exaggerate their talents, crave constant validation, and feel entitled to special treatment. Despite seeming confident, they often have fragile self-esteem and react strongly to criticism or rejection.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, therapist, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or mental health condition. Never disregard professional advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this site.

It’s important to distinguish between clinical NPD and narcissistic traits commonly seen in the general population. Not all confident, ambitious, or self-promoting individuals have NPD.

In clinical psychology, NPD is a categorical diagnosis based on clear criteria, whereas in social psychology, narcissism is seen as a spectrum (Foster & Campbell, 2007).

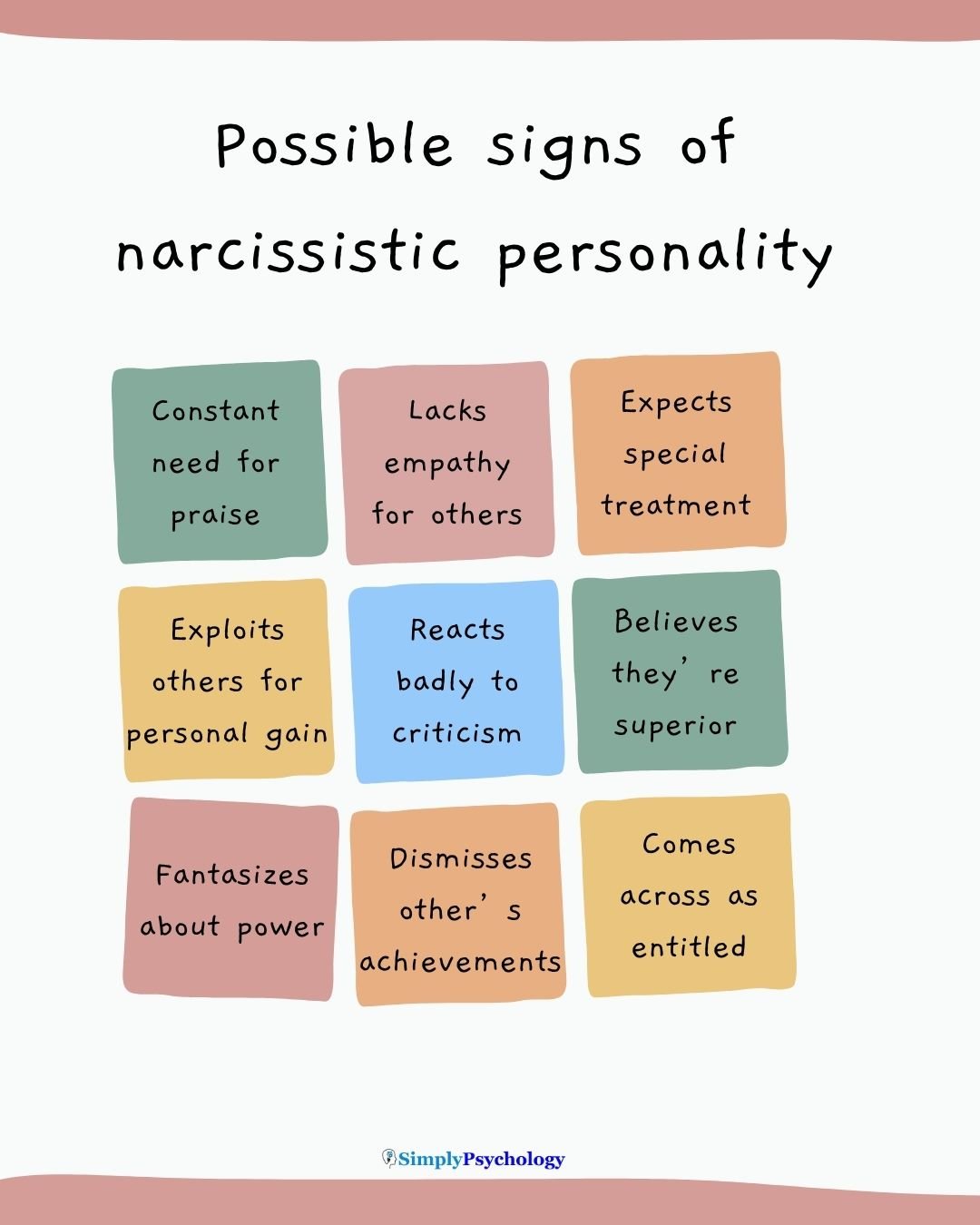

Traits of Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is characterized by a long-standing pattern of grandiosity, a deep need for admiration, and a lack of empathy.

According to the DSM-5, at least five of the following traits must be present for a diagnosis. These traits typically begin in early adulthood and appear in a range of contexts, including work, family, and social life.

Grandiose Sense of Self-Importance

People with NPD tend to overinflate their abilities and expect recognition—even when it isn’t earned.

Example: A coworker may claim to be the most valuable team member, even when others contribute equally or more.

“I make people miserable with my heavy, self‑absorbed energy.”

Fantasies of Unlimited Success or Power

They may be preoccupied with ideas of brilliance, beauty, or perfect love.

Example: A friend might constantly talk about their future fame or wealth, with little realistic action toward those goals.

Belief in Being “Special”

They believe they can only be understood by, or should associate with, high-status people or institutions.

Example: Someone might refuse help from a therapist they see as “too ordinary,” insisting they need a celebrity expert.

Excessive Need for Admiration

A persistent hunger for praise, validation, and attention often drives their behavior.

Example: A parent with NPD might expect constant compliments from their children and become cold or angry if they feel ignored.

“Everything that comes out of my mouth is a subtle brag… The more people distance from me, the angrier I get.”

Sense of Entitlement

They expect special treatment and may become irritated when others don’t meet their demands.

Example: In a group project, they might demand leadership without doing their fair share of the work.

Exploitation of Others

They may use others for personal gain and lack concern for the impact.

Example: A friend may borrow money repeatedly and guilt you for not offering more, never intending to repay it.

“Sometimes I really hate myself for being this way & how people don’t know my real intentions behind my good deeds, while at other times I feel like I want to clone myself & marry me.”

Lack of Empathy

Understanding or caring about others’ emotions is often impaired.

Example: A romantic partner may dismiss your feelings entirely unless the conversation is about them.

“Weak people who don’t try to improve literally disgust me, while I respect the ones who actually put effort into being better ones, even if they don’t necessarily succeed.”

Envy and Belief Others Envy Them

They might express jealousy or assume others are jealous of them.

Example: A sibling might accuse you of being “threatened by their success” if you don’t praise them enough.

“Feeling like god then like shit when you see others doing better than you… feeling empty inside.”

Arrogant or Haughty Behavior

They often come across as condescending, critical, or dismissive of others.

Example: In social settings, they might interrupt or correct people frequently to assert superiority.

These traits are not just occasional behaviors—they form a consistent pattern that can seriously affect relationships, self-perception, and life functioning.

While someone may display narcissistic traits without meeting full criteria for NPD, the disorder involves a persistent and inflexible pattern that causes significant interpersonal or emotional problems.

NPD and Empathy

Research suggests that people with NPD often retain cognitive empathy (understanding others’ feelings) but lack affective empathy (sharing those emotions). This allows them to read people without caring, enabling manipulation and emotional detachment—especially in grandiose narcissism

Types of Narcissistic Personality Disorder

While there’s debate over how many subtypes of narcissism exist, two commonly recognized forms are:

1. Overt (Grandiose) Narcissism

“Characterized by extraversion, low neuroticism, and overt expressions of feelings of superiority and entitlement” (Brogaard, 2019, p. 1).

People with overt narcissism:

- Appear confident, assertive, and socially skilled

- Crave admiration and status

- Believe they’re superior and expect special treatment

- Often pursue success, wealth, or influence

They may come across as charismatic but struggle with empathy and may exploit others to maintain a sense of importance.

2. Covert (Vulnerable) Narcissism

“Reflects introversive self-absorbedness, high neuroticism, hypersensitivity even to gentle criticism, and a constant need for reassurance” (Brogaard, 2019, p. 2).

People with covert narcissism:

- Appear shy, insecure, or emotionally sensitive

- Feel superior but fear rejection or criticism

- Often struggle with depression, trust issues, and envy (Emerton, 2020)

- React with defensiveness or self-pity when challenged

Despite appearing fragile, they still harbor fantasies of greatness or uniqueness and may show little concern for others’ feelings.

Key Difference:

While both types share traits like entitlement, low empathy, and inflated self-image, overt narcissists act outwardly superior, while covert narcissists conceal it behind emotional vulnerability.

How Narcissism Shows Up in Language

Research finds that people with narcissistic personality disorder often use boastful phrases (“I’m the best at this”) or subtly manipulative flattery (“Only someone as smart as you would understand me”). Grandiose narcissists downplay others’ achievements, while vulnerable types use defensive or reactive language, especially when criticized. These patterns reflect deeper issues with identity, empathy, and self-worth.

What Causes Narcissistic Personality Disorder?

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) arises from a complex interplay between genetic vulnerability, early relational experiences, and environmental influences. While no single factor causes NPD, several contributing patterns have emerged in research.

Genetics and Temperament

Twin studies suggest that narcissism has a genetic component. Traits such as emotional sensitivity, impulsivity, and low empathy may be inherited and contribute to vulnerability (Cain et al., 2008). However, genes do not determine destiny—environmental factors also play a major role.

Childhood Experiences

Many individuals with NPD describe early environments that were either neglectful, unpredictable, or excessively focused on achievement. Contributing factors include:

- Emotional neglect or inconsistent caregiving

- Over-praise or excessive expectations tied to performance

- Harsh criticism, leading to fragile self-esteem and perfectionism

These conditions can hinder the development of a stable and secure sense of self.

Attachment and Early Relational Patterns

Attachment theory offers further insight. Children who do not form secure attachments with caregivers may struggle with emotional regulation and self-worth.

Insecure or avoidant attachment styles can foster patterns of emotional detachment, defensiveness, and dependency on external validation—core features of narcissism.

For instance, a child who only receives attention when excelling may learn to equate love with achievement, fueling later entitlement or grandiosity.

Trauma and Identity Instability

Adverse childhood experiences—such as emotional abuse, rejection, or inconsistent parenting—can disrupt identity development. In some cases, grandiosity and control become coping mechanisms to manage vulnerability or shame.

Cultural and Social Factors

Societal values also shape narcissistic traits. Western cultures that emphasize individual success, competitiveness, and appearance may reinforce narcissistic behaviors, particularly in youth.

How Is Narcissism Measured?

While there’s no single gold-standard test, clinicians use several tools to assess narcissistic traits:

- Self-report scales like the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) and Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI) are the most common.

- Clinical interviews (e.g., SCID-5-PD, Diagnostic Interview for Narcissism) help diagnose NPD based on DSM-5 criteria.

- Projective tests like the Rorschach and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) may offer insight but are less standardized.

- Language patterns, such as excessive use of “I” or grandiose statements, are emerging research tools for detecting narcissistic traits.

Most importantly, having narcissistic traits doesn’t mean someone has NPD. A full diagnosis depends on persistent, impairing patterns—not just a few personality quirks.

Treatment

Although treatment for those with NPD can be difficult because these individuals generally do not believe they have a problem, there are options.

The first line of defense, and often best, is psychotherapy. Although the literature on psychotherapy and NPD is still developing, several different types of psychotherapy are used to treat NPD, some of which have been adopted from treatments for borderline personality disorder.

Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP)

This psychodynamic therapy “focuses on unconscious processes as they are manifested in a person’s present behavior” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 1999).

It focuses on the relationship between the clinician and the client, as well as the client’s relationships with the outside world.

The treatment begins with a verbal contract between the two, laying out each member’s roles and responsibilities during treatment. The clinician and the client work together to address any issues the client may have.

Schema-focused therapy

This therapy combines psychodynamic therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is “a short-term, goal-oriented psychotherapy treatment…” whose goals are to “…change patterns of thinking or behavior that are behind people’s difficulties, and so change the way they feel” (Martin, 2016, p.1).

Schema-focused therapy helps replace unhealthy schemas (how the client organizes and interprets information) (Tartakovsky, 2017).

Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT)

Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) has proven effective for many disorders, including NPD. This form of CBT “focuses on mindfulness, emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and relationship skills” (Tartakovsky, 2017, p. 2).

Metacognitive interpersonal therapy (MIT)

This is a type of therapy specifically designed to treat individuals with NPD. In MIT, there are two stages: stage setting and change promoting.

Stage setting involves “gaining a deeper understanding of the person’s interpersonal relationships by exploring different situations, memories, and recurrent patterns.”

Change promoting “includes showing individuals that their ideas do not necessarily mirror reality and that situations can be understood differently when seen from another angle, along with building new and healthier ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving” (Tartakovsky, 2017, p. 2)

Medication

In more severe cases of NPD, medication may be required as well. Clinicians may prescribe mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, or antidepressants to treat NPD patients.

Dealing with Someone With NPD

Being in a personal relationship with someone who has NPD can be challenging; however, it is possible. Here are a few steps to take when interacting with someone with NPD.

Avoid particularly negative interactions (where possible)

Try not to get into conflict with someone who has NPD or purposely try to annoy them.

This may give them ammunition to manipulate, lash out, or possibly “get revenge” on you.

Set healthy boundaries

Those with NPD often do not have healthy boundaries (Kacel et al., 2017) but this does not mean you cannot set your own.

Although it can be scary and difficult, setting boundaries lets those with NPD understand that those who care for them have strong personal values.

Setting boundaries may involve reducing contact with the person, visiting them less often, or communicating to them directly that you will not tolerate their behavior. Make sure to set boundaries carefully, and it is advisable to have someone there as support.

Self-care

Taking care of oneself is important as well. Try practicing yoga, meditation, getting enough food and rest, or doing things one enjoys. It’s important to take care of yourself first before you can care for another.

Consider therapy

If the relationship becomes too stressful to self-manage, individuals are encouraged to seek help. Psychotherapy may help set and maintain boundaries, navigate stress, and feel validated.

Consider ending the relationship

If none of these steps are working effectively, the last option is ending the relationship. This can be an especially important step if the relationship is unhealthy or abusive.

It is important to self-reflect and be honest. If need be, taking a step back may be the best option.

Do you need mental health support?

USA

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

UK

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email jo@samaritans.org .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

116-123

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

Further Reading

- Yakeley, J. (2018). Current understanding of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. BJPsych advances, 24(5), 305-315.

- Baskin-Sommers, A., Krusemark, E., & Ronningstam, E. (2014). Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: from clinical and empirical perspectives. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5(3), 323.

- Kohut, H. (1966). Forms and transformations of narcissism. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic association, 14(2), 243-272.

- Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(4), 590.

- Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Huang, B., Smith, S. M., … & Grant, B. F. (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(7), 1033-1045.

- Ronningstam, E. (2010). Narcissistic personality disorder: A current review. Current psychiatry reports, 12(1), 68-75.

- Caligor, E., Levy, K. N., & Yeomans, F. E. (2015). Narcissistic personality disorder: Diagnostic and clinical challenges. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(5), 415-422.

- Ronningstam, E. (2010). Narcissistic personality disorder: A current review. Current psychiatry reports, 12(1), 68-75.

- Dhawan, N., Kunik, M. E., Oldham, J., & Coverdale, J. (2010). Prevalence and treatment of narcissistic personality disorder in the community: a systematic review. Comprehensive psychiatry, 51(4), 333-339.

References

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28 (4), 638–656.

Di Giacomo, E., Andreini, E., Lorusso, O., & Clerici, M. (2023). The dark side of empathy in narcissistic personality disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1074558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1074558

Elleuch, D. (2024). Narcissistic Personality Disorder through psycholinguistic analysis and neuroscientific correlates. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 18, 1354258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2024.1354258

Emerton, N. (2020, January 08). Narcissistic personality disorder – overt and covert. Retrieved September 08, 2020, from https://www.beu.org.uk/new-blogs/2020/1/8/narcissistic-personality-disorder-overt-and-covert

Foster, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2007). Are there such things as ‘“Narcissists”’ in social psychology? A taxometric analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Science Direct, 1321–1332.

Gunderson, J. G., Ronningstam, E., & Bodkin, A. (1990). The diagnostic interview for narcissistic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47 (7), 676–680.

Kacel, E., Enis, N., & Pereira, D. (2017, August 2). Narcissistic Personality Disorder in Clinical Health Psychology Practice: Case Studies of Comorbid Psychological Distress and Life-Limiting Illness: Behavioral Medicine: Vol 43, No 3.

Konrath, S., Meier, B. P., & Bushman, B. J. (2014). Development and Validation of the Single Item Narcissism Scale (SINS). PLoS ONE, 9 (8).