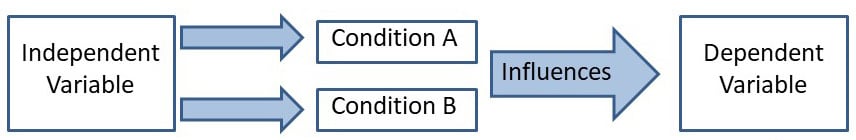

In research, an independent variable is the factor you deliberately change or control, while a dependent variable is the outcome you measure. Think of it as cause and effect — the independent variable is the cause you manipulate, and the dependent variable is the effect you observe.

Key Takeaways

- Variable: Any characteristic, value, or quality that can be observed, measured, or counted. In most studies, there are two main types:

- Independent Variable: The factor that the researcher changes, controls, or uses to group participants to test its effect on another variable.

- Dependent Variable: The outcome (result) that is measured to see if it changes in response to the independent variable.

- Cause and Effect: In experimental research, the independent variable is considered the cause, and the dependent variable is the effect.

- Operational Definition: A precise explanation of how a variable will be manipulated (for an independent variable) or measured (for a dependent variable) in a specific study.

Independent Variable

In psychology, the independent variable is the variable the experimenter manipulates or changes and is assumed to directly affect the dependent variable. It represents the presumed cause in a cause-and-effect relationship and is central to testing research hypotheses.

For example, in a clinical trial, participants might be randomly assigned to receive either a new medication or a placebo.

Here, the type of treatment (medication vs. placebo) is the independent variable, while changes in participants’ anxiety levels form the dependent variable.

Another example is a study on the effects of sleep duration on memory performance, where participants are assigned to sleep for 4, 8, or 12 hours.

In this case, sleep duration is the independent variable, and memory recall—measured by the number of words correctly remembered—is the dependent variable.

In a well-designed experiment, the independent variable should be the only systematic difference between the experimental and control groups.

All other conditions (called extraneous variables), such as environment, instructions, and timing, should be kept constant.

Recognising Independent Variables

To work out if a variable is independent, ask yourself:

-

Is it something the researcher changes or controls?

This could mean assigning people to different conditions (e.g., treatment vs. no treatment) or deciding how much of something participants receive. Sometimes it’s a characteristic – like age group – that’s used to divide participants into categories. -

Does it happen first in the study?

The independent variable comes before any changes in the dependent variable. It’s the starting point that might cause an effect. -

Is the study designed to see if it affects something else?

The independent variable is the suspected “cause” in a cause-and-effect relationship. The researcher wants to know if altering it changes the outcome.

Researchers work with two main kinds of independent variables: experimental variables and subject variables.

1. Experimental Variables

These are variables you can directly change or control in a study.

You might test just two levels (to see if there’s any effect at all) or several levels (to see how different amounts change the result).

Example:

A psychologist wants to test whether mindfulness training can reduce test anxiety in college students. The study has three groups:

-

A group that completes a short mindfulness course

-

A group that completes a full 8-week mindfulness program

-

A control group that receives no mindfulness training

The type and length of mindfulness training is the independent variable, and the level of test anxiety – measured with a standardized anxiety questionnaire – is the dependent variable.

People are randomly assigned to each group so personal differences (like age or fitness) don’t skew the results. This makes it easier to link changes in blood pressure directly to the treatment.

2. Subject Variables

These are personal traits or characteristics people already have and that can’t be changed by the researcher, such as age, gender identity, income, or education.

Because you can’t randomly assign people to have these traits, studies using subject variables are called quasi-experiments.

They can show patterns or associations but can’t prove cause and effect as strongly as experiments with experimental variables.

Example:

A study on how gender identity affects brain activity when hearing infant cries might compare men, women, and people of other gender identities.

The independent variable is gender identity, and the dependent variable is brain activity measured with an fMRI scanner.

Dependent Variable

In psychology, the dependent variable is what researchers measure to see if it changes in response to something else. It is “dependent” on the independent variable, which is the factor the researcher changes or controls.

The dependent variable represents the outcome or result of the study.

Essentially, it’s the presumed effect in a cause-and-effect relationship being studied.

An example of a dependent variable is depression symptoms, which depend on the independent variable (type of therapy).

In an experiment, the researcher looks for the possible effect on the dependent variable that might be caused by changing the independent variable.

Suppose a psychologist wants to find out if listening to music while studying affects how much students remember.

The study environment – with music or without music – is the independent variable, and the number of facts remembered on a test is the dependent variable.

Recognising Dependent Variables

To check whether a variable is dependent, consider:

- Is it the result or outcome being measured?

This is what the researcher is most interested in finding out—such as scores, ratings, symptoms, or behaviours. - Does it change depending on another variable?

If its value could be different based on the condition or group a participant is in, it’s likely dependent on the independent variable. - Is it measured after the independent variable is introduced or changed?

Dependent variables are recorded after the “cause” is applied, so researchers can compare outcomes across different conditions.

Examples in Research Studies

For example, we might change the type of information (e.g., organized or random) given to participants to see how this might affect the amount of information remembered.

In this example, the type of information is the independent variable (because it changes), and the amount of information remembered is the dependent variable (because this is being measured).

Hypothesis 1: Drinking an energy drink before exercise improves running speed.

-

IV: Whether or not the participant drinks an energy drink before exercise.

-

DV: Running speed (e.g., time to complete a set distance).

-

Reasoning: The researcher changes the drink condition and measures its effect on performance.

Hypothesis 2: People who sleep at least 8 hours will score higher on a memory test than people who sleep less than 5 hours.

-

IV: Amount of sleep (≥ 8 hours vs. ≤ 5 hours).

-

DV: Memory test score.

-

Reasoning: Sleep duration is the grouping factor; test scores are measured afterward.

Hypothesis 3: Playing calming music during study sessions reduces anxiety in college students.

-

IV: Study environment (calming music vs. no music).

-

DV: Level of anxiety (e.g., measured with a questionnaire).

-

Reasoning: The researcher changes the environment and measures anxiety afterward.

Hypothesis 4: Smokers have higher resting heart rates than non-smokers.

-

IV: Smoking status (smoker vs. non-smoker).

-

DV: Resting heart rate.

-

Reasoning: Smoking status is a subject variable; heart rate is measured as the outcome.

Hypothesis 5: A mindfulness course will improve focus more than a time management course.

-

IV: Type of course (mindfulness vs. time management).

-

DV: Focus level (e.g., measured with an attention test).

-

Reasoning: The researcher assigns participants to different courses and measures focus afterward.

Learning Check

For the following hypotheses, name the IV and the DV.

1. Lack of sleep significantly affects learning in 10-year-old boys.

IV……………………………………………………

DV…………………………………………………..

2. Social class has a significant effect on IQ scores.

IV……………………………………………………

DV……………………………………………….…

3. Stressful experiences significantly increase the likelihood of headaches.

IV……………………………………………………

DV…………………………………………………..

4. Time of day has a significant effect on alertness.

IV……………………………………………………

DV…………………………………………………..

Operationalizing Variables

Operational variables (or operationalizing definitions) refer to how you will define and measure a specific variable as it is used in your study.

This enables another psychologist to replicate your research and is essential in establishing reliability (achieving consistency in the results).

An operational definition explains in precise, concrete terms what each variable means in the context of a study.

For the independent variable, it describes the conditions or categories participants experience. For the dependent variable, it specifies the method of measurement.

For example, if we are concerned with the effect of media violence on aggression, then we need to be very clear about what we mean by the different terms.

In this case, we must state what we mean by the terms “media violence” and “aggression” as we will study them.

-

Independent variable (manipulated): Type of media content — participants watch either a 15-minute film showing scenes of physical assault (media violence) or a non-violent film (control).

-

Dependent variable (measured): Aggression — the number of electrical shocks a participant chooses to give another person in a controlled setting.

The hypothesis “Young participants will have significantly better memories than older participants” is too vague to test.

A clearer, operationalized version would be:

-

Independent variable (grouping variable): Age group — participants aged 16–30 vs. participants aged 55–70.

-

Dependent variable (measured): Memory — number of nouns correctly recalled from a 20-word list.

The key point here is that we have clarified what we mean by the terms as they were studied and measured in our experiment.

If we didn’t do this, it would be very difficult (if not impossible) to compare the findings of different studies to the same behavior.

Operationalization has the advantage of generally providing a clear and objective definition of even complex variables.

It also makes it easier for other researchers to replicate a study and check for reliability.

Learning Check

For the following hypotheses, name the IV and the DV and operationalize both variables.

1. Women are more attracted to men without earrings than men with earrings.

I.V._____________________________________________________________

D.V. ____________________________________________________________

Operational definitions:

I.V. ____________________________________________________________

D.V. ____________________________________________________________

2. People learn more when they study in a quiet versus noisy place.

I.V. _________________________________________________________

D.V. ___________________________________________________________

Operational definitions:

I.V. ____________________________________________________________

D.V. ____________________________________________________________

3. People who exercise regularly sleep better at night.

I.V._____________________________________________________________

D.V. ____________________________________________________________

Operational definitions:

I.V. ____________________________________________________________

D.V. ____________________________________________________________

FAQs

Can there be more than one independent or dependent variable in a study?

Yes, it is possible to have more than one independent or dependent variable in a study.

In some studies, researchers may want to explore how multiple factors affect the outcome, so they include more than one independent variable.

Similarly, they may measure multiple things to see how they are influenced, resulting in multiple dependent variables. This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the topic being studied.

What are some ethical considerations related to independent and dependent variables?

Ethical considerations related to independent and dependent variables involve treating participants fairly and protecting their rights.

Researchers must ensure that participants provide informed consent and that their privacy and confidentiality are respected.

Additionally, it is important to avoid manipulating independent variables in ways that could cause harm or discomfort to participants.

Researchers should also consider the potential impact of their study on vulnerable populations and ensure that their methods are unbiased and free from discrimination.

Ethical guidelines help ensure that research is conducted responsibly and with respect for the well-being of the participants involved.

Can qualitative data have independent and dependent variables?

Yes, both quantitative and qualitative data can have independent and dependent variables.

In quantitative research, independent variables are usually measured numerically and manipulated to understand their impact on the dependent variable.

In qualitative research, independent variables can be qualitative in nature, such as individual experiences, cultural factors, or social contexts, influencing the phenomenon of interest.

The dependent variable, in both cases, is what is being observed or studied to see how it changes in response to the independent variable.

So, regardless of the type of data, researchers analyze the relationship between independent and dependent variables to gain insights into their research questions.

Can the same variable be independent in one study and dependent in another?

Yes, the same variable can be independent in one study and dependent in another.

The classification of a variable as independent or dependent depends on how it is used within a specific study. In one study, a variable might be manipulated or controlled to see its effect on another variable, making it independent.

However, in a different study, that same variable might be the one being measured or observed to understand its relationship with another variable, making it dependent.

The role of a variable as independent or dependent can vary depending on the research question and study design.

How do independent and dependent variables work in non-experimental or observational studies?

In non-experimental or observational studies, researchers don’t actively manipulate the independent variable.

Instead, they observe natural differences that already exist and look for patterns or relationships between variables.

The independent variable is still the one thought to influence the outcome, but it’s based on pre-existing conditions, behaviours, or traits—such as age, gender, income level, or lifestyle habits—rather than being assigned by the researcher.

The dependent variable is still the outcome being measured, but in this case, researchers can’t be as confident about cause and effect.

This is because other factors, called confounding variables, might also influence the result.

Example:

A psychologist might study whether exercise frequency is linked to stress levels.

Here, exercise frequency (independent variable) isn’t controlled by the researcher – it’s just recorded as reported by participants.

Stress levels (dependent variable) might be measured using a questionnaire.

The study could show that people who exercise more tend to report lower stress, but it can’t prove that exercise alone causes the difference.

Recognize Common Mistakes

- Mixing up cause and effect: A frequent error is thinking the variable you measure (dependent) is the cause, when in fact it is the effect. Always identify which factor is changed or controlled (independent) and which responds (dependent).

- Assuming correlation means causation: Just because two variables change together does not mean one causes the other. Only well-controlled experiments can establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Overlooking control variables: Forgetting to keep other factors constant can make it hard to know if changes in the dependent variable are truly due to the independent variable.

- Using vague or undefined variables: Failing to operationalize variables can lead to confusion or make replication impossible. Clearly define how each variable will be measured.

- Switching roles between studies: The same variable can be independent in one study and dependent in another. Always decide based on the specific research question.

| Feature | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Role in the study | The “cause” — what the researcher changes, controls, or uses to group participants. | The “effect” — what the researcher measures to see if it changes. |

| When it happens | Comes first in time — occurs before the dependent variable is measured. | Comes after the independent variable has been applied or varied. |

| How it changes | Changed or chosen by the researcher, or based on pre-existing traits (in quasi-experiments). | Changes naturally as a possible result of the independent variable. |

| Examples in psychology | Type of therapy (CBT, medication, control group) | Level of depression symptoms after treatment |

| Examples in everyday life | Amount of sleep (4, 6, or 8 hours) | Number of mistakes made on a test the next day |

| Key question to ask | “Is this the thing I’m changing or comparing between groups?” | “Is this the thing I’m measuring as the outcome?” |